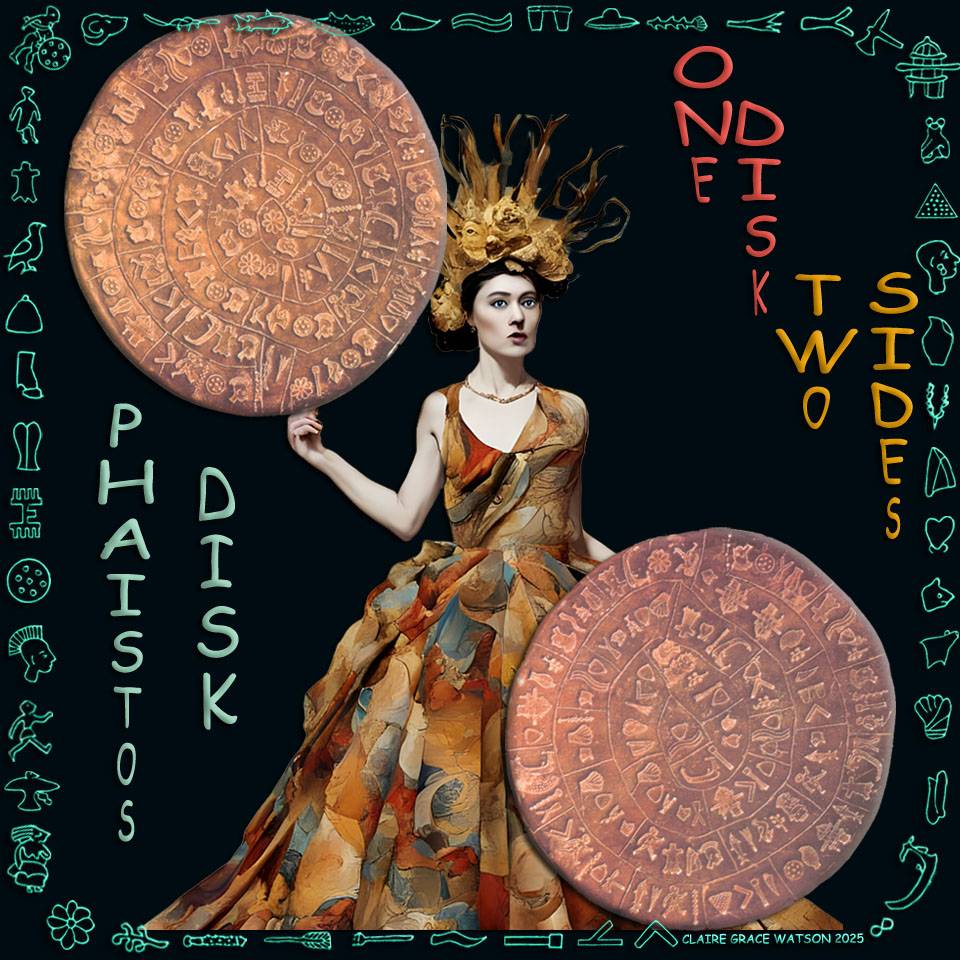

The history surrounding the Phaistos Disk and its discovery is fascinating. The two-sided

terracotta disk from the Mediterranean Bronze Age was found in 1908 beneath the burned-down Phaistos Palace, Crete, in a basement corner accessible by a trap door above. Beside the disk was a tablet of Linear A writing (undeciphered) of ancient Crete, likely explaining it. Fire-hardened,

perhaps by the fire, the Disk is an anomaly in a Minoan world of sun-baked

pottery. One of archaeology's greatest mysteries, it is, like the universe, a

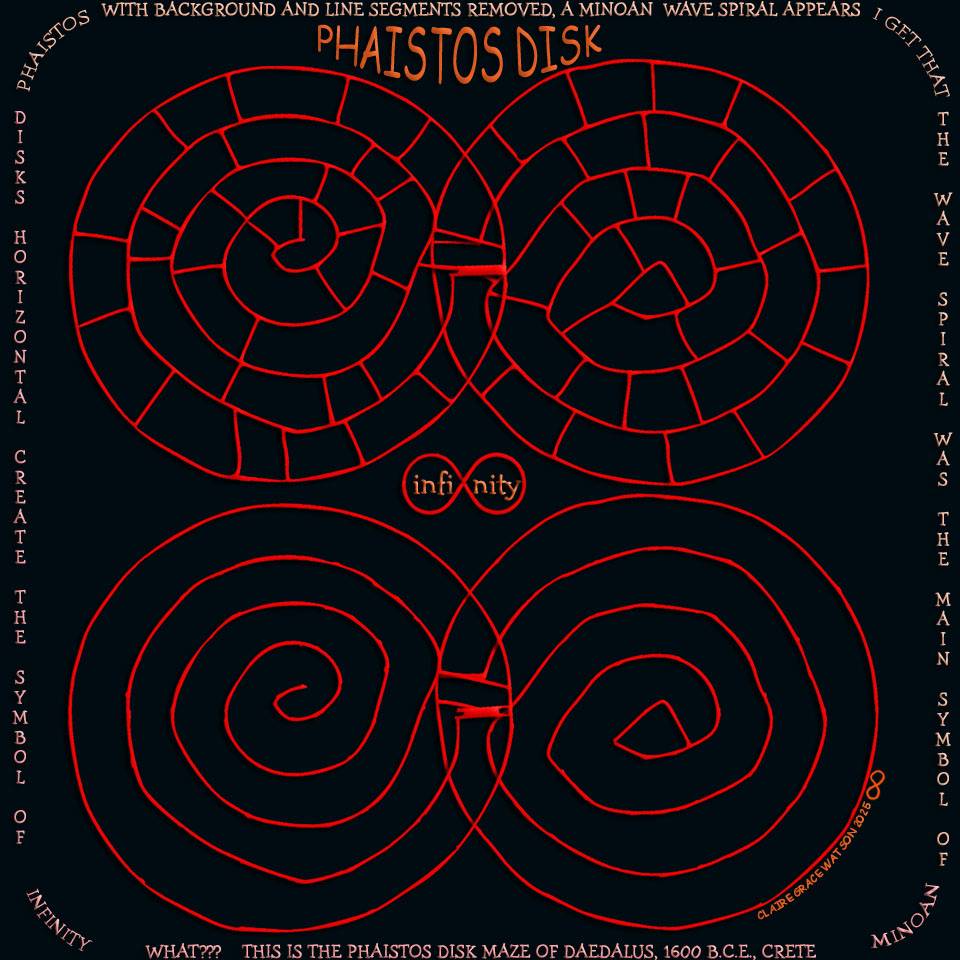

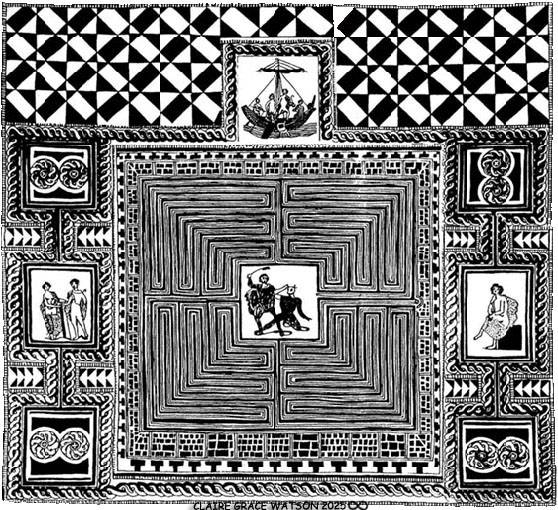

masterpiece of both concealment and revealment. From out of this ancient world, from exactly the same time and the same place, comes the other renown mystery, the Maze of Daedalus. Are the Phaistos Disk and the Maze of Daedalus the same thing? In the Phaistos Disk we have the artifact but not the narrative, and in the Maze of Daedalus we have the narrative but not the artifact. They fit together like interlocking puzzle pieces, figuratively and literally.

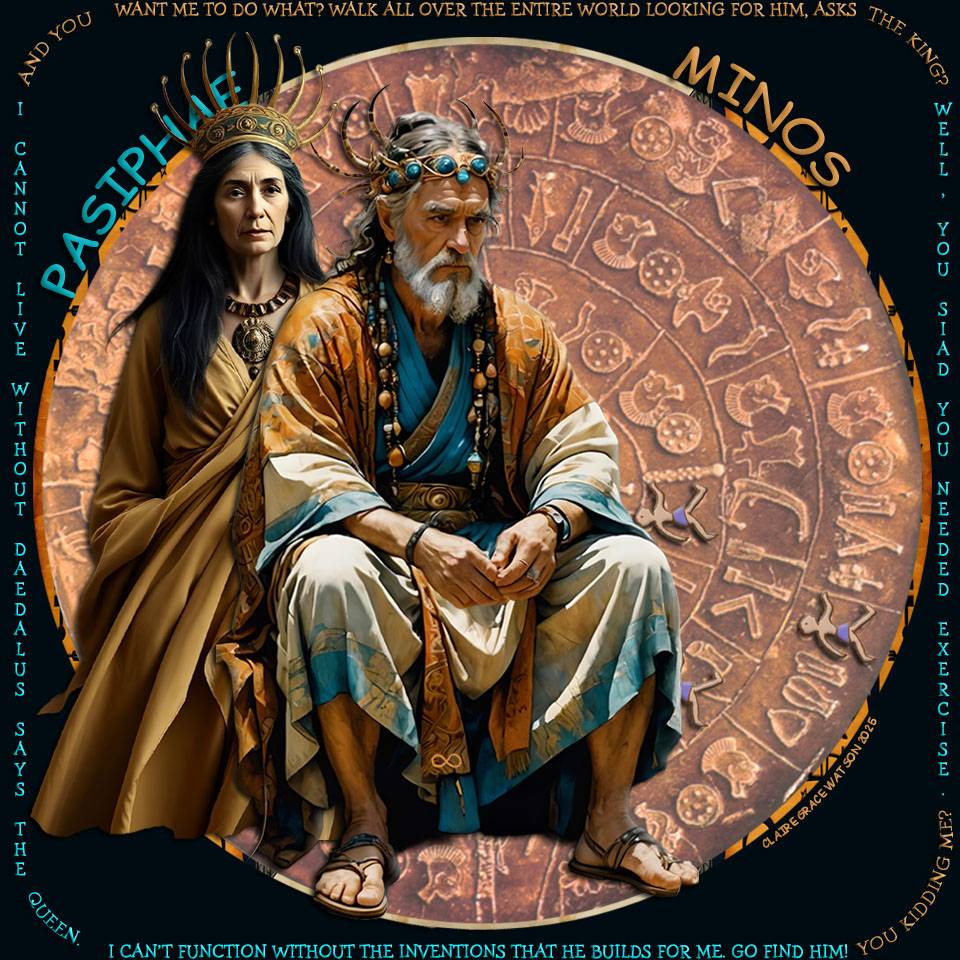

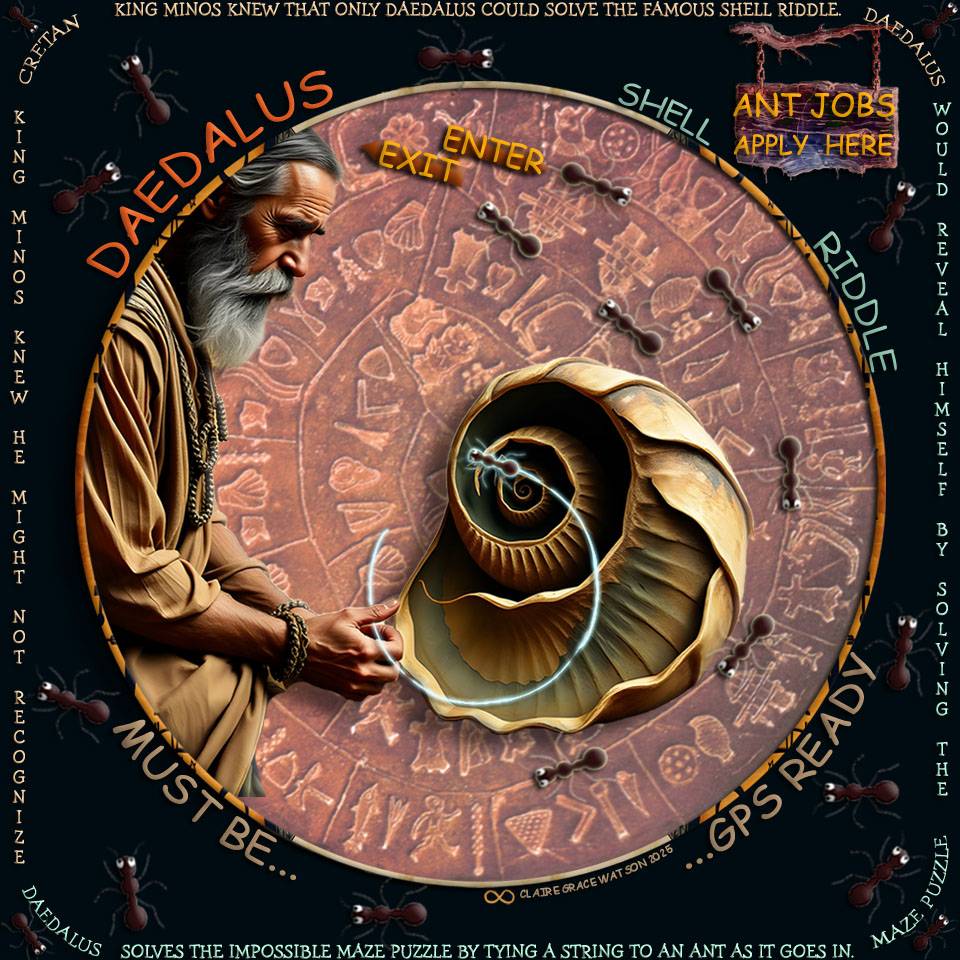

As King Minos searched for Daedalus he carried with him a seashell puzzle, called the Shell Riddle, and asked everyone he met to solve it. He knew that only Daedalus could solve the riddle, and this was how he meant to identify him since he might be much changed in appearance.

"Minos, meanwhile, searched for Daedalus by traveling from city to city asking a riddle. He presented a spiral seashell and asked for a string to be run through it. When he reached Camicus, King Cocalus, knowing Daedalus would be able to solve the riddle, accepted the shell and gave it to Daedalus. Daedalus tied the string to an ant which, lured by a drop of honey at one end, walked through the seashell stringing it all the way through." (Wikipedia, Daedalus)

If the Phaistos Disk is the spiral seashell, and the spirals of the

Disk are the string running through, then archaeology's greatest mystery can be solved. This same string, in fact, becomes much more famously known as Ariadne's Thread

in a late Bronze Age fiction written by Plutarch based on the Shell Riddle and involving Theseus, a Minotaur, and a maze. The

riddle, in all cases of the myth, is the same - how to get all the way through the seashell to find the honey, or through

the maze to escape the Minotaur, or through the Disk to solve the maze.

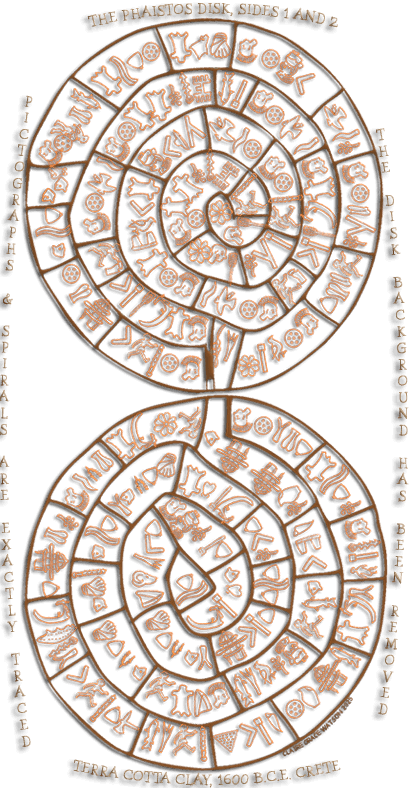

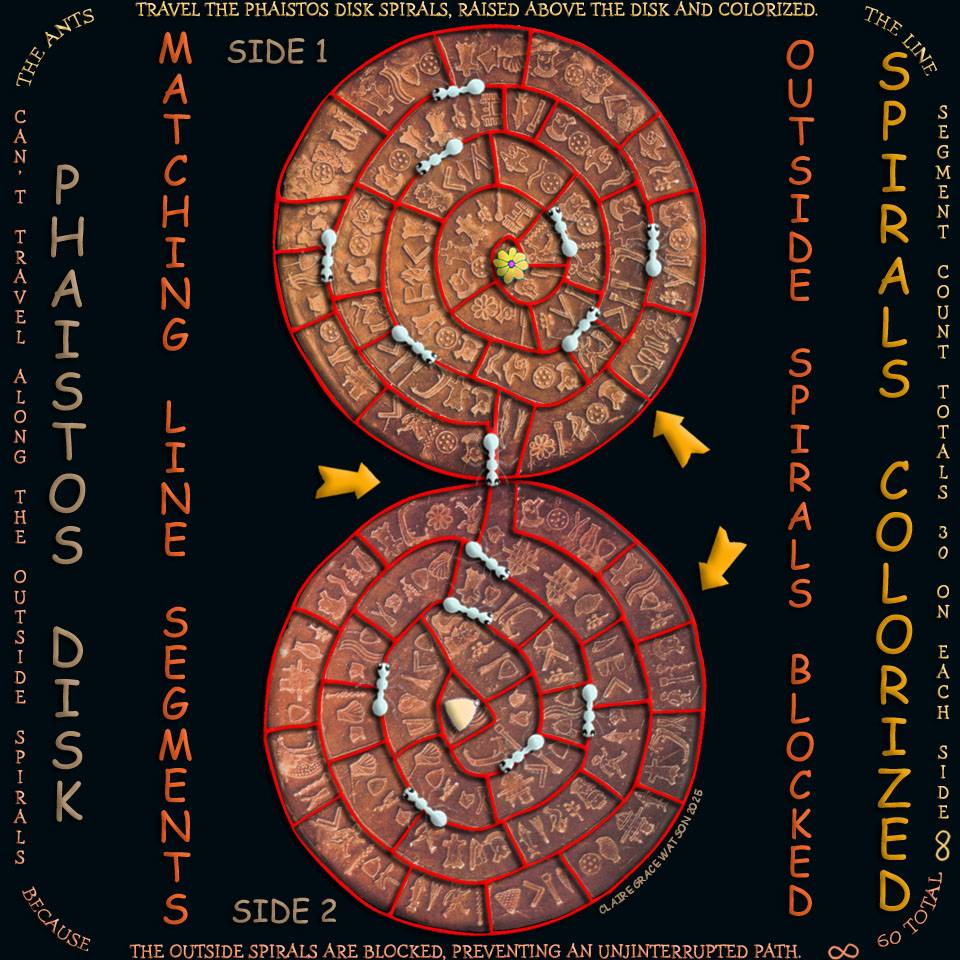

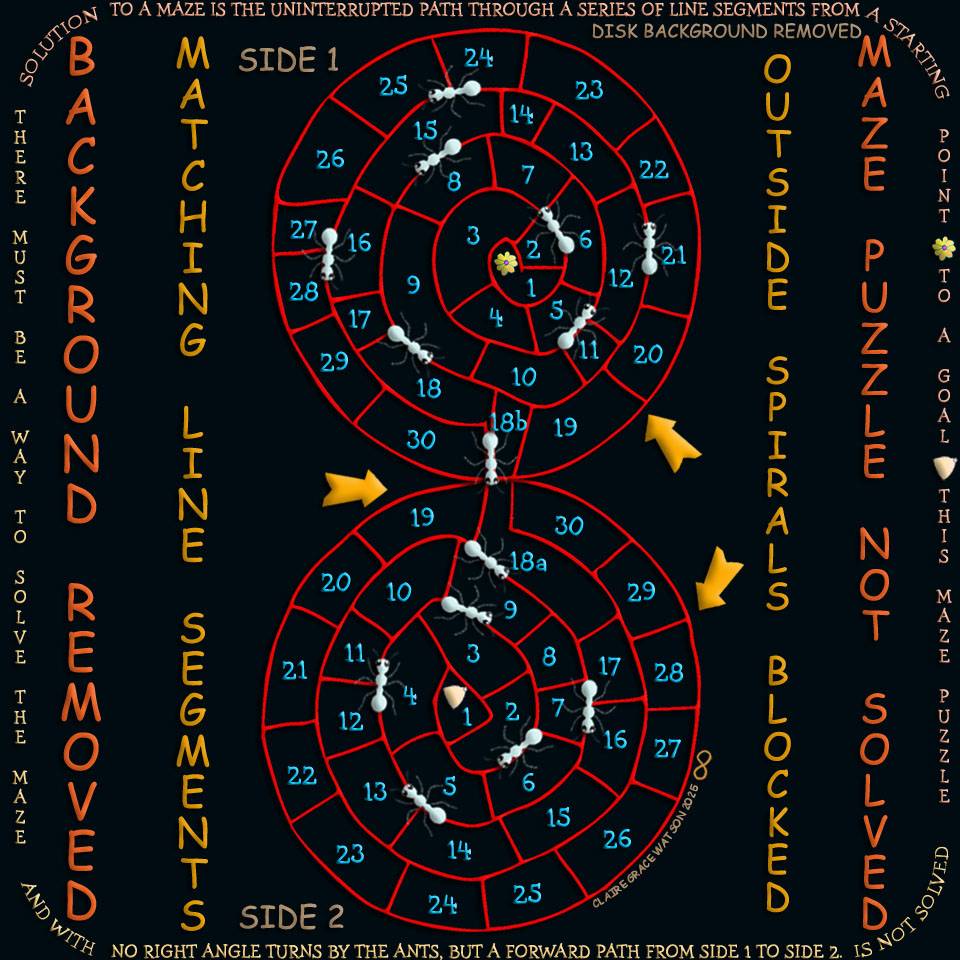

The solution to a maze puzzle is the uninterrupted path through a series of intricate line segments from a starting point to a goal. This maze puzzle, the Shell Riddle, is not solved until the outside spirals of the seashell are part of the uninterrupted path from the center of Side 1 (flower/sun) to the center of Side 2 (honey pot/star.) The Shell Riddle is solved only when the ants can easily travel to the honey pot in a uninterrupted, straightforward manner that includes the outside spirals (edges of the Disk).

SOLVE THE SHELL RIDDLE

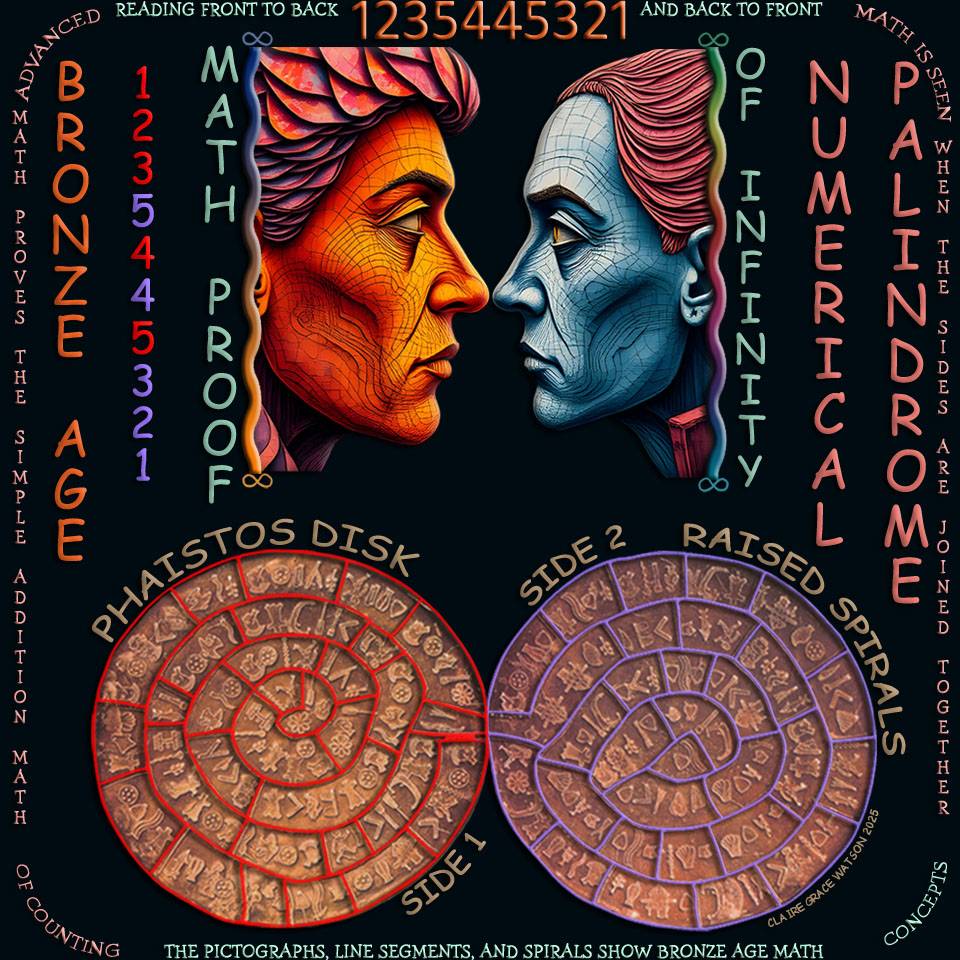

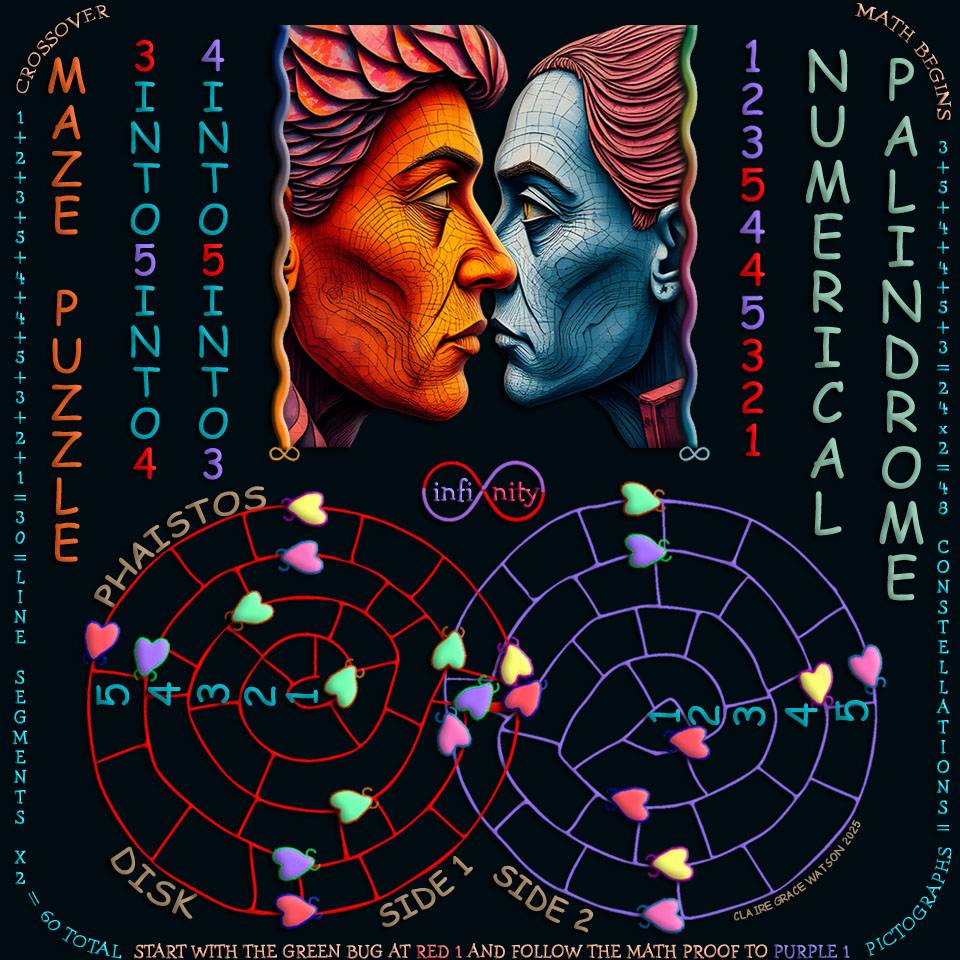

The Phaistos Disk, a world-renowned enigma, comes from Minoan Crete, about 1600 BCE, the ancient civilization famous for naming our constellations and for the Maze of Daedalus. The artifact is terracotta pottery, about 6" in diameter and 1" thick, only a little larger than a CD, with 2 inscribed sides and 2 spirals per side, each spiral with 5 rings (10). The spirals are divided into 60 line segments (30 Side 1, 30 Side 2). The outside spirals have 12 line segments (24 outside); inside spirals have 18 (36 inside). Divided among the line segments and etched into the disk are 48 unique tiny pictographs, the same number as our ancient constellations, and most of them are replicated to create 240 pictographs. 37 are created to appear identical and are repeated various times. 11 are unrepeated.

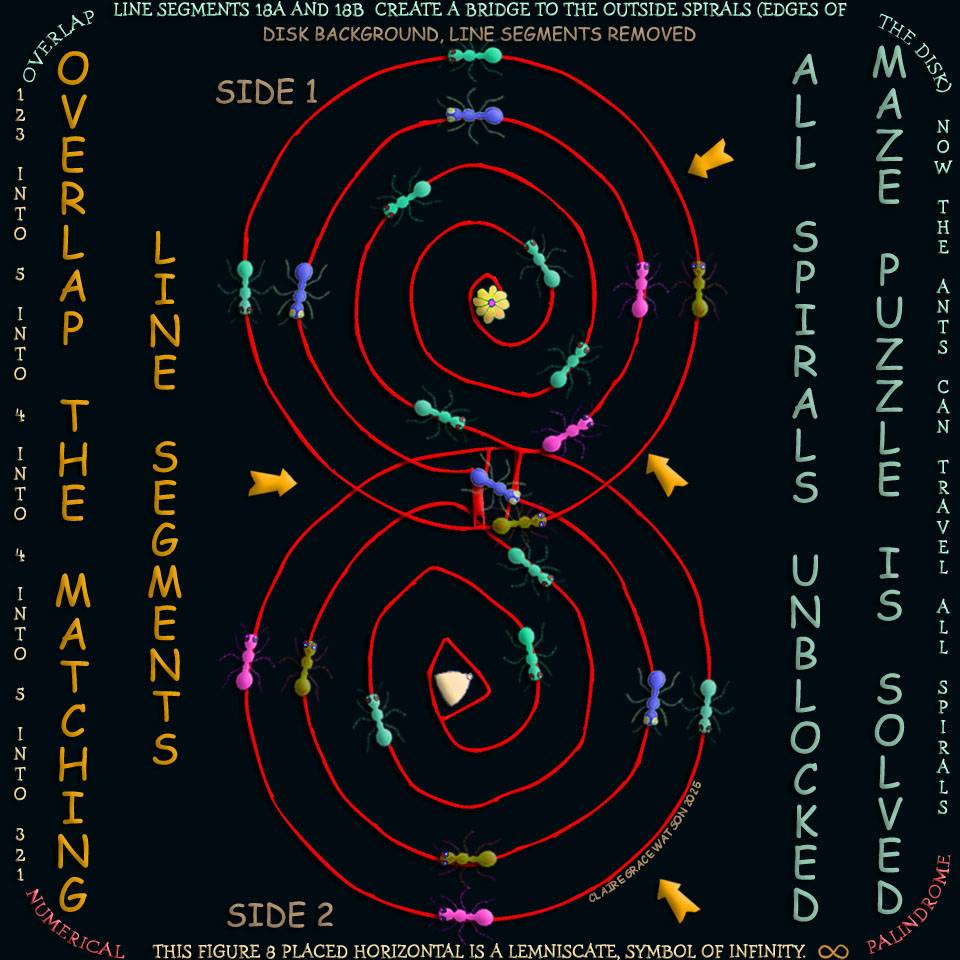

Though the Disk seems a puzzle and chaotic, a concept of Mediterranean Bronze Age ideas on mathematical symmetry has been gained just by counting the pictographs, the spirals, and the line segments. This simple arithmatic is supplanted by an advanced math involving multiplication and division once the two sides are joined together. The advanced math functions as an argument that proves the simple addition arrived at by the counting of spirals, line segments, and pictographs. This new math expresses as an architectural representation of infinity by way of a numerical palindrome - 1235445321. Reading front to back and back to front, the numbers prove infinity or endlessness in Minoan mathematicians' (or at least this pottery artist's) understanding of paradox in using a finite line segment to prove infinity, as a line can be divided infinitely.

Beginning at the crossover section where the two sides of the Disk are joined together, the palindrome crossover math, by natural addition, 3+5+4+4+5+3 = 24 (the total number of line segments on the outside spirals of both sides) divided by 2 = 12 (the total number of line segments on the outside spirals of each side). Then, 24 multipled by 2 (the number of sides) = 48 (the total number of unique pictographs and ancient constellations). Also, the entire palindrome 1+2+3+5+4+4+5+3+2+1 = 30 (the total number of line segments on each side of the Disk) x 2 (the number of sides) = 60 (the total number of line segments both sides of the Disk).

"And in these sixty spaces dwell the souls, each one according to its nature, for though they are of one and the same substance, they are not of the same dignity." (Plutarch)

Inside these 60 "soul spaces" are the souls - the 48 unique pictographs connected to the 48 ancient constellations. The math argument proves both itself and infinity and is therefore, from the point of view of a Bronze Age mathematician, beyond dispute, using the sciences available during that time in the world.

The 48 souls/pictographs are replicated to appear identical because, when connected by lines like creating constellations by connecting stars, they create larger pictographs that include some of the constellations to which each soul is connected, as well as all of the geometry used to build the greatest of structures upon which to stand to get closer to these constellations - the Great Pyramid.

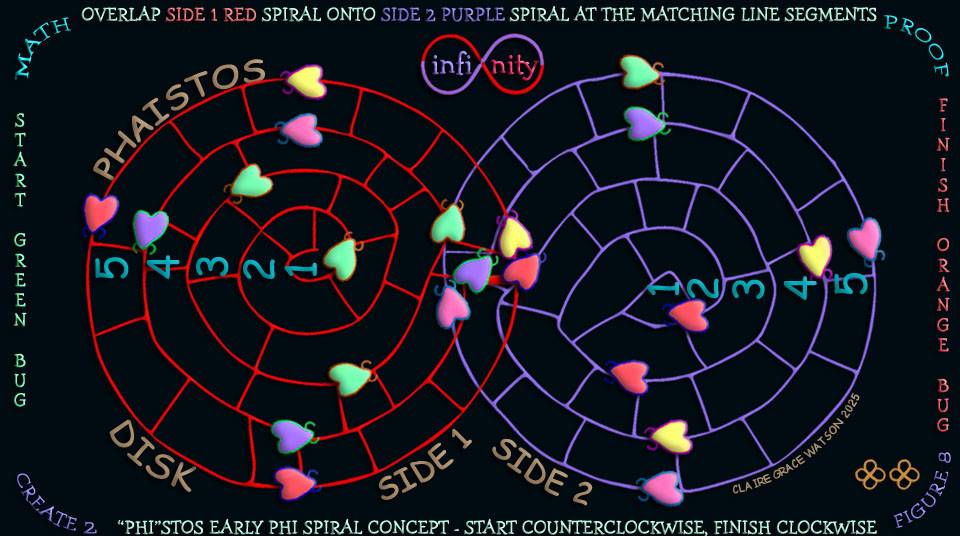

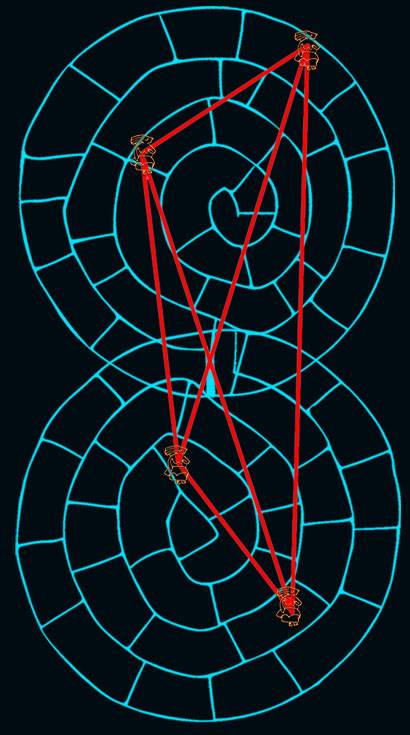

To solve the maze and experience the palindrome, overlap Side 1 onto Side 2 (red spiral on top of purple spiral) at the matching, connecting line segments. Next, start at the center of Side 1, then move counterclockwise. Cross over from Spiral 3, Side 1, to Spiral 5, Side 2 (green bug), and move clockwise. Cross over from Spiral 5, Side 2, to Spiral 4, Side 1 (pink bug) and move counterclockwise. Cross over from Spiral 4, Side 1, to Spiral 4, Side 2 (purple bug), move clockwise. Cross over from Spiral 4, Side 2, to Spiral 5, Side 1 (yellow bug), move counterclockwise. Cross over from Spiral 5, Side 1, to Spiral 3, Side 2 (orange bug), move clockwise and travel to the center of Side 2, creating the shape of a figure 8, twice. Return in the same pattern. (1, 2, 3 into 5, 5 into 4, 4 into 4, 4 into 5, 5 into 3, 2, 1)

The maze puzzle has been solved, the numerical palindrome math proof of infinity established, the meaning of the Minoan wave spirals that decorated the palaces is revealed and, most significantly, the architecture of the celestial realms is revealed and it is based upon principles of geometry - all of this certainly worth preserving for posterity in fire-hardened terracotta.

This is perhaps the original idea regarding the layered architecture of the celestial realms involving three important layers, as elucated 2,000 years later by Early Common Era Gnosticism. They are the Hebdomad (7), the Ogdoad (8), and the Ennead (9). On the Phaistos Disk is a theory regarding the layered architecture of the Ogdoad, the eighth sphere or aeon - with its continuum concept. Where before 10 spirals were visible, 5 each side, now they have become 8 with the overlap, the number of the Ogdoad ("Eighth Sphere") where reside the Egyptian gods Isis and Osiris and now proved irrefutably to exist by the mathematics on the Disk. The Ogdoad is marked by the brightest star in the sky, Sirius. In Minoan mythology Sirius is the Minoan creation goddess Rhea (Chaos).

"Philosophy [nature] is written in that great book which ever is before our eyes -- I mean the universe -- but we cannot understand it if we do not first learn the language and grasp the symbols in which it is written. The book is written in mathematical language, and the symbols are triangles, circles and other geometrical figures, without whose help it is impossible to comprehend a single word of it; without which one wanders in vain through a dark labyrinth." (Galileo)

This nearly-lost, antique, math-based mythology is preserved by Plotinus, philosopher founder of Neoplatonism, and Plutarch, philosopher priest at the Temple of Apollo at Delphi, and the Phaistos Disk of Minoan Crete. Plotinus (1,300 years after the Phaistos Disk) and Plutarch (1,500 years after the Phaistos Disk) both give accounts of an ancient worldview involving a numerological outlook passed down from Crete.

This outlook involves the math-based origin of both the universe and humanity. Formed in the womb of the Minoan creation goddess, Rhea (Chaos), were 5 cosmoi (main divisions or layers of cosmic stuff, the 5 spirals each side of the Disk), and into these layers or firmaments formed 60 soul spaces (total number of line segments on the Disk) made of 60 types of soul-stuff, comprising 240 individual souls (total number of pictographs on the Disk) made of 48 "ark types" (ships of the sky or constellations and total number of unique pictographs on the Disk).

It isn't just the mathematics that stands out in the math proof, but also the art. The Phaistos Disk puts the art in artifact as it creatively delivers complex information in a simple way, based on the Minoan love of mazes and their creation of

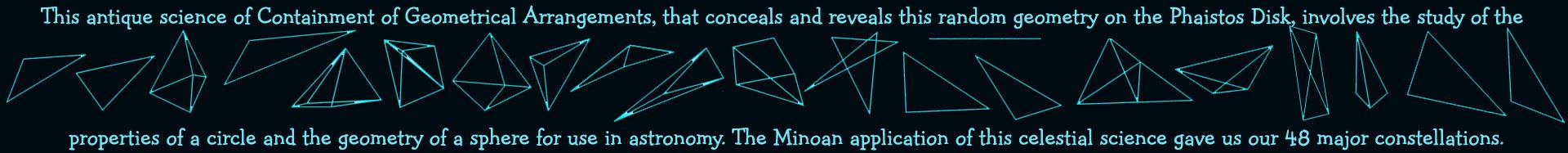

our 48 original constellations by connecting stars with lines. And, it makes use of an invisible dimension to continue its revelations about the Minoan world via large, hidden pictographs. The hidden dimension is arguably its main revelation and certainly its most surprising one, because it delivers into this mix of philosophy and science the Minoan concept of parallelism, by introducing another dimension proved by this math - a hidden dimension parallel to our visible one. In order to achieve this, the artist employed in pottery the mostly forgotten, and nearly lost, antique Mediterranean Bronze Age science "Containment of Geometrical Arrangements."

This "earthly" science, that involved the study of the properties of a circle (containment) and the geometry of a sphere (geometrical arrangements), was extended to early astronomy. The circle/sphere of containment is the Phaistos Disk and the geometrical arrangements are the large pictographs created by connecting matching pictographs with lines, as in created constellations in astronomy. The artist documents the relationship of geometry with astronomy, showing the sameness of the two sciences. Aligned this way, and used to diagram and interpret both earth and sky, these sciences together can produce an offspring, a kind of power that is Metaphysics - a vision of the invisible - capable of occupying the mind of a savant like Pythagoras. This philosophy, transcendent of the geometry, astronomy, and mathematics visible on the Phaistos Disk, and concealed behind it, engaged Pythagoras for the entirety of his life and created him as a mystic. It lead Plotinus to found Neoplatonism and it encouraged Plutarch to reside as a priest at Delphi, the name reminiscent of both Phaistos and Phi spiral.

"...in those days [of ancient Egypt] of initiate kings and rulers and sages who occupied themselves with the Sacred Science,

when the clear Aether spake face to face with them without disguise, or holding back aught, in answer to their deep scrutiny of holy things." (Thrice-Greatest Hermes, G.R.S. Mead)

It also reveals, in total, eight significant and complex images or larger pictographs concealed on the disk, that exact number foretold by the Figure 8 design of the graphical math proof of infinity, again forming a mathematical symmetry. By this method is the invisible dimension revealed, populated with larger, more significant pictographs.

Images above from left to right: Constellation Argo, Star Sirius and Seven Planets, Great Pyramid Exterior, Great Pyramid Interior, Great Pyramid - Apex, Base, and Two Sides, Great Pyramid Warrior Perimeter (with Shields), Right Triangle, Diameter

As a point of interest, the Phaistos Disk may demonstrate the beginning of the ancient philosophy of the "indwelling pattern" that became popular with the Sethian Gnostics of Early Common Era Gnosticism nearly 2,000 years later, and is known to us as modern astrology, our socially popular version of celestial science. The idea is that each individual has their own unique pattern that indwells them and determines who they become and what they do. That pattern is invisible to the human eye, just as are the patterns hidden on the Phaistos Disk, and the "souls" gain that pattern by resonance with a higher power. In our times, as in the Minoan world view, that higher power is a constellation, but we don't conceive of it as a divine being as they did.

In addition to math proofs and hidden patterns, the Phaistos Disk may document the integration of ancient calendars known to the Minoan world.

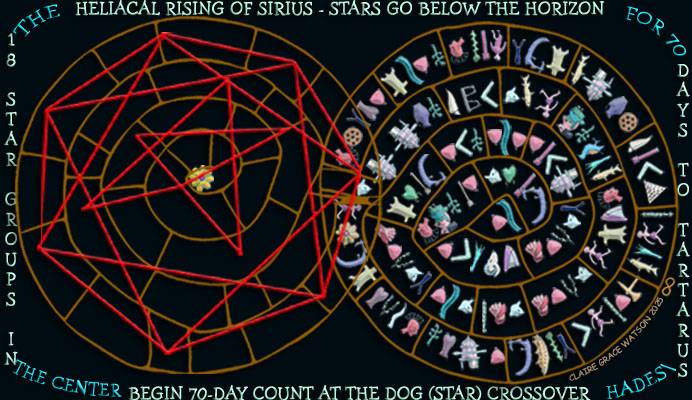

The Disk may also preserve a zodiac stellar calendar based on star groups. Star groups might be arranged in groups of 12,

along the outer edge. These might be the 12 constellations we are most familiar with today in our popular astrology that are historically accepted as identified by Minoan

Crete. 18 more spiral out from the center of Side 1 and Side 2, for a total of 36 groups or decans, each one rising above the dawn

horizon for 10 days, totaling 360 days.

18 star groups spiral into the center (18 line segments of the inner spirals) as they move into the underworld of Tartarus/Hades (go below the horizon) for 70 days before they reappear. 70 is the exact number of pictographs, beginning at the crossover from Side 1 to Side 2, counting from the first pictograph met with in spiral 4, the dog, "dog star", an ancient symbol for Sirius. Therefore, each one of these pictographs represents a day in which the star Sirius, seen rising with the sun on Side 1, has now disappeared from the sky on Side 2. The Sothic (Sirius) year lasted from one sighting of Sirius in the dawn of a new year until the next year on the same day. Heliacal rising of Sirius will occur again at the flower on Side 1 in an infinite cycle, as represented by the infinity symbol created when the two sides of the Disk are joined together at the matching, connecting line segments. Set this calendar to the first sighting of Sirius each year to keep it current.

Observation of the

movement of star groups would let the Minoans tell time at night because the decans would rise 40 minutes later each night. When reckoning time at

night, only 12 decans (and annual divisions) were used (our signs of the zodiac), delineated by the 12 line segments along the edge of the Disk, although 18 were taken into account, those delineated in the center of the

Disk by the 18 line segments. With the addition of a 10 day intercalary month every two years, a 365-night stellar year can be accounted for.

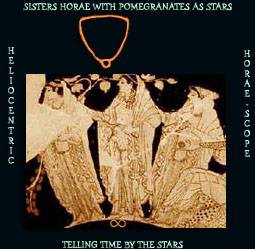

Long after the Phaistos Disk was created, the Greeks gave the name Helios to the god of the measurement of time. He had several sister goddesses called Horae, goddesses of the cycles of Time who reigned over the revolution of the constellations by which the passing seasons were measured. The Horae were honored by farmers, who would hoe the ground, plant and tend their crops according to

the location of the stars in the skies. (The Horae, above, hold pomegranates/stars, pictograph on the Disk.) Because the Horae surrounded the throne of Helios, this method of

timekeeping is a heliocentric horae-scope or horoscope, meaning to observe time or the seasons. This method of keeping "star" time points to the Sothic calendar, a wide-spread

Egyptian method of keeping time by tracking the star Sirius instead of the sun.

If the two sides of the Phaistos Disk have application as Minoan integrated calendars, taken together they might be a

Lunisolar calendar with 12 months and, every two years, the periodic intercalation of a 13th month, the interlinking line segments.

Side 1, the solar calendar, keeps track of the three seasons, each of four months duration, along the 12 line segments of the outer edge, in the same location as the star groups.

A count of the daylight hours or divisions of each day could also be kept on this side of the Disk, counting 12 divisions/hours along the

outside edge with the 12 months and the seasons of the year.

Side 2, the lunar calendar, keeps time in lunar months (moonths), a moonth being the time between the four phases of

the moon - new, waxing, full and waning. The lunar calendar has 12 moonths of 30 days for a 360-day year. The first month and new year might

begin in the summer on the heliacal rising of star Sirius in 1600 BCE, approximately the equivalent of our July 1. Alternately, the Minoans may

have had 30 months of 12 days - the 30 line segments each side, 12 of them on the outside spiral. Every two years the 13th month would occur and

it would be only 2 days shorter than the others.

The combined Lunisolar calendar might have worked this way; one month solar, one month lunar, moving from side to

side of the Disk, until 24 months had passed, at which time the intercalary or 13th month would begin the biennial festival of Dionysus in

Minoan Crete in which the drama of his life was re-enacted.

When did the first logic of infinity occur to us collectively and when was it first represented as a horizontal figure 8? Could it have been during the Minoan civilization? The integrated calendars may not have been intended to work this way, but if we wanted to keep time in these different ways we could if we

had the Phaistos Disk. And we could even have a Sothic calendar.

Sothic is the Greek word for Sirius, which the Egyptians called Sopdet or Sopdu. A Minoan

calendar/Phaistos Disk would be unique in that it may have solved the problem of keeping accurate time when tracking star Sirius.

All Sothic calendars were known to have 12 months of 30 days. Some Sothic calendars may have had 30 months of 12 days.

Both presented the Egyptian timekeepers with a problem -- a year of 360 days -- so they had to add 5 days at the end of the year to have a 365-day year so

that the calendar would work right.

The Egyptians had a whole mythology that went with these 5 extra days/gods, which were festival days in Egypt and perhaps Crete,

when the birth of these gods was celebrated. With the extra 5 days added, the Egyptian Sothic calendar would start again the following year

on or about the same important day -- the heliacal rising of Sirius -- the day the star first rises with the sun. But the Sothic cycle was 1468 years because that is how long it takes for the calendar to recoup that day that was lost every 4 years from having a 365 day year.

The Phaistos Disk may be a Sothic calendar that keeps accurate star time, and it

may be the only physical one in existence. There may be something unique about this Sothic calendar. Instead of having 12 months of 30 days, it

may have alternating months of 30 and 31 days, (counting the connecting line segment as a day of the month rather than an intercalary month) more

like our calendar than like the Egyptian calendar. Around the outside edge of the Disk are the 12 solar and the 12 lunar months. The solar months have 31 days and the lunar months have 30 days. The 2-sided Disk/calendar

represents a two-year period, at the end of which was held the festival of Dionysus in which his life was celebrated.

This method of keeping time would be incredible if you consider what is known about Sothic calendars. It means that the Minoans may

have figured out how to adjust a Sothic calendar so it kept proper star time and avoided the "Sothic cycle" of 1468 years.

When you look at our calendar you see something odd about it. The months don't alternate 30 and 31 days

every time, and February has only 28 days. Then, every four years we add a day to make up for the fact that our year is really 365 and 1/4 days,

and that ends our cycle. Our calendar is only off by a 1/4 of a day each year and we are

unaffected by that as long as we correct periodically.

The Minoans may have taken exactly the same approach. The difference is, while the Egyptians had years of 360 days and we have years

of 365 days, the Minoans may have had years of 366 days. Rather than add 5 days at the end of the year and then have a calendar that rights itself

every 1468 years, the Minoans may have had alternate months of 30 and 31 days. Then, they subtracted a day at the end of every two years, and that kept them

within a 1/2 day of accuracy and ended their cycle. Instead of adding 5 festival days at the

end of the year, like the Egyptians and their civil calendar, they may have celebrated them along with the Egyptians as festival days that occurred for them at the beginning of their

year with the heliacal rising of Sirius. Then, every 2 years they held their own festival of Dionysus on the "subtracted" day, a day that didn't exist at all because it wasn't on their calendar - perfect for a wild, Dionysian bacchanal!

By their subtraction method of timekeeping, the Minoan calendar would be simple and correct. If it really worked this way it would have given them a huge

advantage over the rest of the Aegean world and might explain in part their fantastic civilization. Their calendar would always have been a little ahead

instead of a lot behind. Additional to their world view might have been the enlightened idea that time and the stars are dieties we can shape, using our imagination and the tools of geometry, to become more than mere subjects of them.

With these calendars working together, and with Oceanus, the World Ocean encircling the world and connecting these calendars together in a neverending wave spiral, infinity is accounted for, represented by the infinity symbol created by interlocking both sides of the Disk.

1,600 years after Minos Palace, Plutarch wrote "Life of Theseus," enshrining that Maze of Daedalus revision into history. He said he was trying to envision a hero to parallel the Roman, Romulus. Plutarch's story of Theseus, Ariadne, and the Minotaur is believed to be a late Bronze Age invention, 500 years after the Disk was made, created perhaps because the story of an ant's progress through a spiral seashell lacks suspense. Perhaps storytellers could have embellished the travels of the king, how he found Daedalus all ragged and shoeless and wracked with grief, barely able to commandeer an ant. But that still would not compete with a hero lost in a maze, battling a Minotaur to the death, and sailing away with the lovely Ariadne. Times haven't changed that much; adventure still beats contemplation. If Theseus existed long enough to sail away, he did so high up over the Aegean, becoming Jason in the process.

Daedalus lived in a culture that rose from a neolithic condition via technology with the smelting of iron, the importation of

metals, the use of bronze and the development of boats and ships that sailed all over the Mediterranean. They apparently traded with various

countries, including Egypt where murals have been discovered recently that depict the Minoans bringing gifts to the pharaoh. The Minoan

culture was replete with brilliant artisans.

Was Daedalus the creator of the Phaistos Disk, or was Daedalus the collective name of the brilliant Bronze Age artisans who

lived and worked back then? Perhaps Daedalus means Inspiration. They were so incredibly creative that it makes me wonder if Crete is the

root word for create. They created palaces, designed mazes, made bronze armor and weapons, painted beautiful murals, made exquisite pottery,

designed drainage systems, built trading ships, paved their roads with shells and rocks and became advanced astronomers. They were very

artistically advanced, with the creation of ceramics and carved ivory, tile mosaics and mazes, and rudimentary hieroglyphic writing.

And they had a fascination with bulls. Not just at Knossos, where the palace roof

tops were trimmed in bull's horns and the walls display images of bull sports, but also other places like Mallia, where the palace is designed

like the head of a bull. And then, of course, there is the legend of the Minotaur, a half-bull, half-human creature

contained by Daedalus inside the famous maze.

Another mystery surrounding the Disk is how it was made. Perhaps Daedalus means "cunning artificer" because he could invent not just the thing itself but the way to

make it, as well. Daedalus was so clever that he is said to have invented images. He was the Leonardo da Vinci of his day and even more so.

Daedalus was inventing during the Mediterranean Bronze Age when, from our perspective, so many inventions seem possible. Everything was

new then, relative to da Vinci's day. For Daedalus it must have been truly a world of opportunities, a wide-open vista of possibilities

for the inventor.

"Daedalus (=cunning artificer) was a sort of personified summary of mechanical skill." (H.G. Wells)

It is difficult, however, when

reading all the mythology and legends associated with Daedalus, to state exactly what he invented. A list of his inventions begins with a lurid tale that

Greek adults perhaps told in saunas to pass the time. Poseidon, god of the sea and special god of Plato's Atlantis, presented King Minos

with a white bull and Queen Pasiphae (Persephone) with a problem, which Daedalus solved. The king's wife is supposed to have lusted

after the bull! Pasiphae asked Daedalus, the palace architect, to design a bed

for the mating to take place. Daedalus complied and the result of the mating was the Minotaur, half-bull, half-human.

Centuries passed and the legendary status of Daedalus the inventor grew. The stories surrounding him became unrelated

to his inventions, but beyond inventing a maze, a bedchamber, wings and images, Daedalus cannot be said to have invented anything that

would justify his extraordinary status as the world's greatest inventor. The invention of images, however, would certainly qualify this

inventor for legendary status, but it seems his reputation rests on his most famous invention, the Maze of Daedalus, which is lost in time.

We have only mythology to tell us what his maze was and what its purpose was, but mythology is storytelling of the highest order and not

recorded history at all. We just know he invented an incredible maze in Crete during a period of time before written history.

Had he invented a way of recording a history of his time, so that he could record some of the events and some of his inventions,

that would be very helpful, but he also would have to invent a way to do it and a way to preserve it for thousands of years. If he was truly

worthy of his legendary status as inventor, he would have done that. This cunning artificer could invent not just the thing itself but the way to

make it, as well. The Phaistos Disk could be his greatest invention, the one for which he is best known and which records his other inventions

including how he made it and why he is credited with inventing images.

If the Phaistos Disk is the Maze of Daedalus, then the great inventor deserves his star status and more because the disk may

record his inventions that seem now lost to us. They included images, telescopes, binoculars, textbooks in clay, calendars, a printing press, a kiln, mazes, an historical record,

geometries, constellations, world-disks, and even a new world view of an old world. He may also have realized spatial relativity and created an

object to demonstrate it. If so, it has taken nearly 4,000 years for his inventions and ideas to become known because that is about how long

the Phaistos Disk was lost.

The Phaistos Disk may not be the Maze of Daedalus, but nothing will ever come as close to it as this Disk. I am also encouraged

to embrace this theory because it is so much easier to talk about the Phaistos Disk if we allow it to be the Maze of Daedalus and if we interpret

the mythology of Daedalus literally and allow that he actually lived in Minoan Crete and flourished there because there were so many more people like him/her, Minoans with incredible artistic and mechanical skills.

After 32 years studying this enigmatical artifact, I have come to the conclusion that a pottery artist in Minoan Crete left us an artifact designed to give us an indepth view of Minoan Crete - their world view, their ancient sciences of astronomy, geometry, and mathematics, of which they were masters, and their timekeeping methods, of which they were innovators. This artifact also demonstrates their belief in the existence of an invisible dimension as well as preserves the ancient, mythological maze puzzle, the Maze of Daedalus. Ultimately, the "Phaistos Disk Maze of Daedalus" is a math argument that illustrates the Mediterranean Bronze Age math proof that the universe is a math structure, in fact a math maze, comprehensible through the "celestial sciences" which were their the integrated sciences of mathematics, geometry, and astronomy.

A DARK LABYRINTH

IS THIS THE MAZE OF DAEDALUS?

There can be no doubt it is a maze but is it the most famous maze in history? An investigation of the ancient myth of the Daedalus maze proves revealing. The original Daedalus myth, from Greek mythology that began in the Minoan

civilization, involves the Shell Riddle. This myth tells the story of a distraught inventor, a sad queen, and a problem-solving king. At the urging of his wife, King Minos of Crete went searching

for Daedalus, the renown inventor and favorite of Queen Pasiphae. Daedalus was wandering the world in grief, and the king and queen were much concerned. A tragedy had occurred.

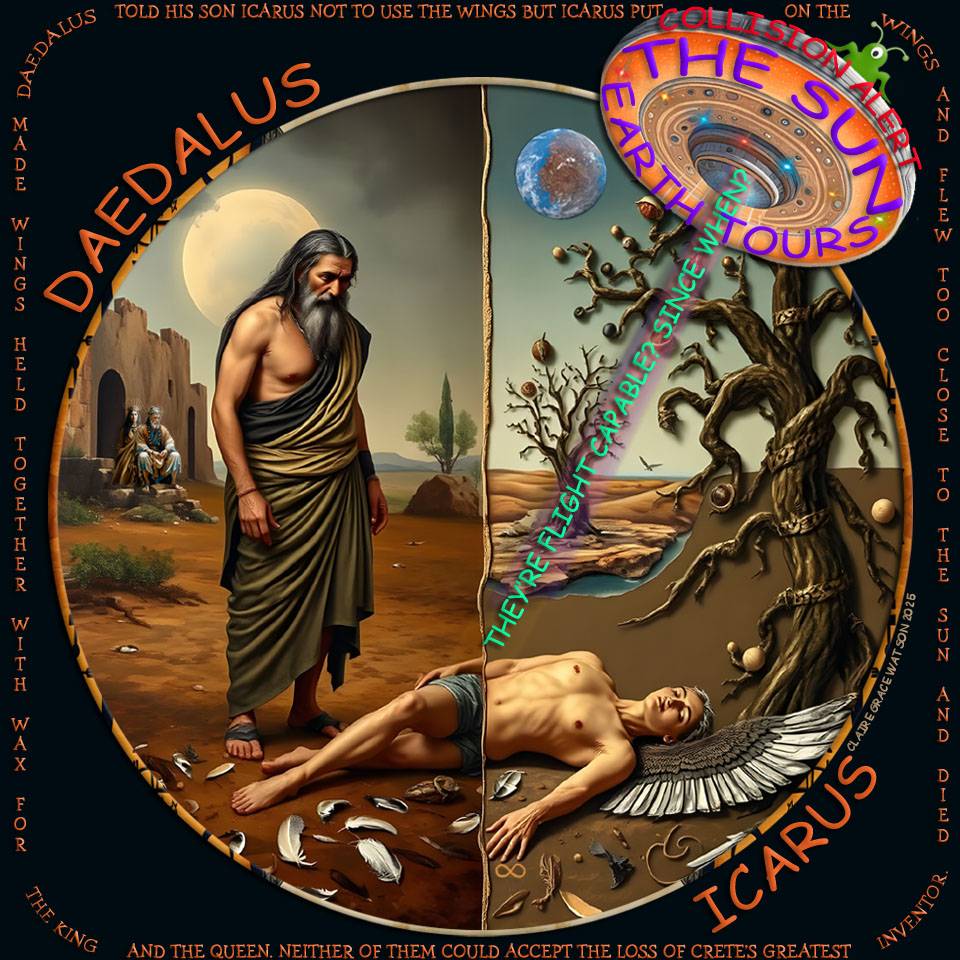

Daedalus had invented remarkable wings fashioned of feathers and wax and designed to give flight to whomever wore them. While he was busy working on a project for the queen, his son Icarus put on the wings and flew too close to the sun. When the wax melted Icarus crashed and died.

Daedalus had invented remarkable wings fashioned of feathers and wax and designed to give flight to whomever wore them. While he was busy working on a project for the queen, his son Icarus put on the wings and flew too close to the sun. When the wax melted Icarus crashed and died.

Daedalus, in his grief, blamed himself and wandered the Aegean world mourning the loss of his son. "After burying Icarus, Daedalus traveled to Camicus in Sicily, where he stayed as a guest under the protection of King Cocalus." (Wikipedia)

Daedalus, in his grief, blamed himself and wandered the Aegean world mourning the loss of his son. "After burying Icarus, Daedalus traveled to Camicus in Sicily, where he stayed as a guest under the protection of King Cocalus." (Wikipedia)

THE SHELL RIDDLE

THE SHELL RIDDLE

(Spoiler alert! Next image shows the solution.)

CELESTIAL SCIENCESBRONZE AGE MATH PROOF OF INFINITY

CELESTIAL SCIENCESBRONZE AGE MATH PROOF OF INFINITY

FOLLOW THE MATH PROOF

FOLLOW THE MATH PROOF RIDE THE ROLLER COASTER

RIDE THE ROLLER COASTER ARCHITECTURE OF THE CELESTIAL REALMSSAME SUBSTANCE, NOT THE SAME DIGNITY

ARCHITECTURE OF THE CELESTIAL REALMSSAME SUBSTANCE, NOT THE SAME DIGNITY

48 UNIQUE PICTOGRAPHS/SOULS/ARK TYPES

AND NUMBER OF TIMES THEY ARE REPEATEDTHE AETHER SPEAKS

INVISIBLE DIMENSION REVEALED BY

CONNECTING MATCHING PICTOGRAPHS Taking a clue from this unique, unrepeated pictograph (left, man holding a shield with seven tiny circles in the shape of a hexagram), the connect-the-dots approach of viewing the disk reveals the numerous and common (to us) plane geometries expected to be seen, 1,300 years before the Greek mathematician and geometer Euclid. Revealed are diameter, right triangle, cone, every kind of triangle, rectangles, polygons, parallel lines of same length and different length.

Taking a clue from this unique, unrepeated pictograph (left, man holding a shield with seven tiny circles in the shape of a hexagram), the connect-the-dots approach of viewing the disk reveals the numerous and common (to us) plane geometries expected to be seen, 1,300 years before the Greek mathematician and geometer Euclid. Revealed are diameter, right triangle, cone, every kind of triangle, rectangles, polygons, parallel lines of same length and different length.

MINOAN CALENDARS - ZODIAC STELLAR,

MINOAN CALENDARS - ZODIAC STELLAR,

LUNISOLAR, SOTHIC, 366-DAY-YEARZODIAC STELLAR CALENDAR

MINOAN LUNISOLAR CALENDARMINOAN SOTHIC CALENDAR

MINOAN LUNISOLAR CALENDARMINOAN SOTHIC CALENDAR![]()

Sirius rose with the sun on about the same day every year, their July 19th, the sun perhaps represented by the 8-petaled "Flower" at the center of Side 1. Just like we add one day in February every leap year to

make our calendar and our sun work in conjunction, the Egyptians added 5 days at the end of their year and tracked the movement of a star

rather than the sun. The star's movement is so close to that of the sun that the star calendar worked the same as a sun calendar. One is a

lunar calendar and the other is a solar calendar.

Sirius rose with the sun on about the same day every year, their July 19th, the sun perhaps represented by the 8-petaled "Flower" at the center of Side 1. Just like we add one day in February every leap year to

make our calendar and our sun work in conjunction, the Egyptians added 5 days at the end of their year and tracked the movement of a star

rather than the sun. The star's movement is so close to that of the sun that the star calendar worked the same as a sun calendar. One is a

lunar calendar and the other is a solar calendar.

![]()

![]() Just as night follows day, night perhaps represented by the "Star" at the center of Side 2, the Egyptians and perhaps the Minoans had calendars with

solar months and lunar months.

MINOAN 366-DAY-YEARDAEDALUS, CUNNING ARTIFICER

Just as night follows day, night perhaps represented by the "Star" at the center of Side 2, the Egyptians and perhaps the Minoans had calendars with

solar months and lunar months.

MINOAN 366-DAY-YEARDAEDALUS, CUNNING ARTIFICER

Maze of Daedalus based on Plutarch's "Life of Theseus" ![]() Daedalus also invented the maze in which

innocent young Greeks were fed to the Minotaur wherein they wandered lost until eaten. In another variation of the purpose of his maze,

he built it for King Minos of Crete in order to contain the Minotaur, who was the queen's son. He also is credited with inventing attachable

feathered wings, held together with strings and wax, so that humans could fly (pictograph left). With these wings he

and his son Icarus escaped his own inescapable maze by flying out of it. When Icarus flew too high, the sun melted the wax.

Daedalus also invented the maze in which

innocent young Greeks were fed to the Minotaur wherein they wandered lost until eaten. In another variation of the purpose of his maze,

he built it for King Minos of Crete in order to contain the Minotaur, who was the queen's son. He also is credited with inventing attachable

feathered wings, held together with strings and wax, so that humans could fly (pictograph left). With these wings he

and his son Icarus escaped his own inescapable maze by flying out of it. When Icarus flew too high, the sun melted the wax.

Daedalus invents images. Stare at the triangles

and watch them flip. How many triangles are there? CONCLUSION- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

![]() Unpacking and publishing the Phaistos Disk since 1993

Unpacking and publishing the Phaistos Disk since 1993 Copyright Notice - Disk of the World - Text and images copyrighted March 21, 1993-2025, Claire Grace Watson, B.A., M.S.T., U.S. Copyright and under the Digital Millennium Copyright Act of 1998, All rights reserved. No part of this web page may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means without written permission from the author, except for the inclusion of brief quotations in a review.

Copyright Notice - Disk of the World - Text and images copyrighted March 21, 1993-2025, Claire Grace Watson, B.A., M.S.T., U.S. Copyright and under the Digital Millennium Copyright Act of 1998, All rights reserved. No part of this web page may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means without written permission from the author, except for the inclusion of brief quotations in a review.