In 1993 I came home to Atlanta, Georgia from the North American Bridge Championships, a competition I always enjoyed and still sometimes do. In bridge, the main thing you do in order to have a chance at winning is you visualize the cards you can't see in your opponents' hands and then deduce probable suit patterns based on the cards you can see in your own hand. You put what you can see with what you can't see together then bid and play the hand accordingly. When you're right about suit patterns you score better than when you're wrong. My mind had been developed that way through 22 years of playing tournament bridge, so it was working like that when I first saw a picture of the Phaistos Disk. I recognized it as a puzzle and just automatically looked for hidden patterns. Right away I saw something and of course became fascinated by it. I was captured in its spirals and I stopped playing bridge regularly for the next 20 years. Bridge just couldn't compete with the Phaistos Disk in terms of being a great puzzle.

Puzzles and mysteries, especially ancient mysteries and mysticism, always intrigued me. I got that genetic from my grandmother on my father's side. I have memories from when I was a small child of sitting at the dining room table with her watching her work a crossword puzzle. Coming home from the bridge tournament, I went to the library, where I liked to hang out and study mysteries, to research the Great Pyramid of Giza, to find something more about its purpose as an archaeoastronomy site. I always enjoyed reading books about it. There had always been conjecture that the ancient Egyptians used the Great Pyramid for religious rituals, and being so interested in the mysterious Egyptian mystery schools and their religion, I pulled several books from the shelves to flip through them.

Ancient Unsolved Mysteries may have been the name of the book. It contained many pictures of mysterious objects, among them a large image of the tiny Phaistos Disk, a two-sided pottery artifact created about 1600 BCE during the Minoan civilization of the island of Crete, in the Aegean Sea. Here was the "most famous undeciphered artifact in archaeology," it said. Written above it were the words, "Who can read the Phaistos Disk?"

One of the pictographs on the disk stood out for me. It resembles a carpenter's square (left) and seemed familiar. I had seen it on another image entitled the Maze of Daedalus in that same book. I considered that to be a pattern. That's when it occurred to me, what if I could find patterns on the Phaistos Disk? Just at that moment, a dream I had the night before flashed in my mind and I remembered an old man with a beard saying to me, "There is a secret bridge. You will become the bridge."

One of the pictographs on the disk stood out for me. It resembles a carpenter's square (left) and seemed familiar. I had seen it on another image entitled the Maze of Daedalus in that same book. I considered that to be a pattern. That's when it occurred to me, what if I could find patterns on the Phaistos Disk? Just at that moment, a dream I had the night before flashed in my mind and I remembered an old man with a beard saying to me, "There is a secret bridge. You will become the bridge."

I convinced myself that twenty-two years of solving bridge hands, combined with a graduate degree in English language with a concentration in myth and saga, gave me a better chance than most of solving this new puzzle, world-famous though it was as being unsolvable. Nothing new was known about it after 100 years of efforts and, even more challenging, the civilization that produced it is considered "lost." This only inspired my competitive nature. Who doesn't want to do what's never been done? I was on it like a duck on a june bug, as my grandmother used to say about a new crossword puzzle!

Before I researched the disk I evaluated my chances of success by studying the approach of the people making decipherment attempts. You do this in bridge. When you're serious, before you play you study those who went before you, the ones who left a trail via bridge books - what they did, what they knew, what they thought, what they figured out. All of those people who came before me and tried to decipher the Disk, and couldn't, all believed the same thing, that the pictographs on the Disk are the Minoan version of Egyptian hieroglyphs and, because they are situated inside the spirals, they are to be read in a spiral. For them, the only question is, which way do you read them, from the center spiraling out or from the outside spiraling in? Like a field of bridge players all taking the same wrong approach to the play of a hand, the decipherers collectively never veer from their wrong approach. They think it's the percentage approach so they stick with it.

But it's possible, and happens often in bridge, that in a field of players where everyone gets it wrong, one person will take an anti-percentage approach and get it right. More people would do that, I believe, if they didn't run up against such strong peer pressure to always take the percentage approach and let go the rare times when the anti-percentage approached actually works. That never stopped me in bridge from going the opposite direction of the crowd. And as a child I was always coloring outside the lines. I have been that one person so often in life that I thought I could be that one person with the Phaistos Disk as well.

But I think it was the I00 years of endless debates about whether to read the pictographs from the center spiraling out or from the outside spiraling in that made me feel I had a real chance. Endless debates in bridge are called post-mortems and are sometimes more about pontificating than analysis. Even more so with the Phaistos Disk. Almost everyone uses the Disk as a podium to stand upon and have their opinions and themselves be taken seriously. They never see it as a puzzle that can be solved. Like in bridge, they see it as an opportunity to advance themselves as a person of importance. With such a clear field, I did not hesitate. I planned to have it solved before the next bridge nationals, held three times a year. The next one was three months away. Because of the Phaistos Disk I missed that one and most of the ones that have followed. As of this moment (2025) I have been working on the Phaistos Disk for 32 years. That's a lot of missed Nationals and I don't regret it, either.

The first mistake they make, those would-be decipherers, is they all assume the spirals on the disk have no other purpose than to organize the pictographs. Like bridge players who think the suit colors are red and black just to keep the suits separated, neither see the colors or the spirals as information by themselves. And even though the disk is a two-sided artifact, nothing is ever said about the relationship of one side to the other, whereas I thought of each side of the disk as similar to a hand in bridge. One side is your hand and the other is your partner's hand, and the idea is to bridge the two hands to see how they fit together so you can get the big picture and make best use of the cards. When you take the anti-percentage approach with the Phaistos Disk, you get this puzzle solution and something remarkable - a Bronze Age math proof of infinity in the form of a numerical palindrome. This conflicts strongly with our arrogant notion of these ancient people as being quasi-Neolithic, yet here it is.

The first few years I was researching the Phaistos Disk my mother would tell me I was wasting my time while my father was quietly interested in my research. Maybe my mother was right, financially speaking. I did turn down a well-paid position as head of data management in Human Resources at Hewlett Packard in Atlanta so I could move to St. Augustine, Florida and get a job waiting tables so my mind would be completely free of junk and I could focus on the Disk. I didn't tell them that, though. I made up some story about how the company was trying to force my hand regarding the employment contract.

Now, I live in HUD housing as a result of that decision but the place suits me. It's secure and I can afford it, and I don't have to listen to people on the elevator talk about their portfolios. In fact, the people I meet on the elevator are blessedly free of that capitalistic edge and are more interested in peace and quiet, which works for me. I'm free to work on the Phaistos Disk in a quiet environment. If I'm not working on it I'm thinking about it, turning it over in my mind trying to grasp what the artist was preserving in clay. It's an oasis that I go to in my mind. Even with the advancements I was making that I showed my parents, who were a quite taken aback by it, they were still disappointed that I wasn't ensconced at Hewlett Packard blissfully managing their data. They had other plans for me and they thought that I was living below my capabilities. I disagree with that but I was certainly living below their expectations. They came from a different world than the one I lived in. They were part of the Greatest Generation, and that generation had big plans for their kids.

I grew up in the United States, in a small south Georgia town in the middle of a swamp. I spent most of my time fishing and hunting, camping and hiking, and running from spiders and snakes. Also chasing me at one time or another were hornets, wasps, wild hogs, mad dogs, giant woodpeckers, and a panther. When I wasn't outside in swamp world I was inside reading a book or playing cards.

When I was eight I learned to play penny poker, taught to me by my Dad's fishermen buddies in our river cabin down on the Altamaha River. In the beginning they won a lot of my pennies (I had an infinite supply) and they also took me fishing with them and taught me how to catch just about every kind of fish in the river. When I was a teenager I bought a bass boat and kept it on the river so I could go fishing on the weekends by myself.

I remember one time going to get my boat out, and some high school guys were hanging around the boathouse and found a Black snake. One of them threw it at me so they could laugh when I ran, but I caught it in my right hand and threw it right back at them and had a big laugh when they scattered! That was the day I took the boat out to investigate the legend of the gorilla on Bald's Island (below), supposed to have been seen sitting on a log reading a newspaper and sipping gin. I was sure I could solve this puzzle.

Bald 's Island is a dense, spooky jungle island off the river a bit and back into the swamp. I tied up at the bank under a willow tree and got out and walked around the island looking for gorilla tracks. That was the day the huge Water Moccasin fell off the tree branch into my boat and almost directly on top of me. I am proud to say I did not jump out of the boat or turn the boat over. I did rock the boat violently when I beat the snake to death with the boat paddle. I also did a good bit of screaming that was likely unsettling for the wildlife on the island, including the gorilla that I never did find, or its tracks, either.

When I turned 16, Dad gave me a 28 gauge shotgun and my grandfather gave me a .22 caliber rifle, both specially fitted to my shoulder. Dad took me quail hunting and dove shooting with the shotgun and I was always the only girl in the group. He took me squirrel hunting and taught me how to shoot a squirrel mid-flight from tree to tree with the rifle. I insisted that we cook and eat whatever we killed, so he had me clean the fish, skin the squirrels, pluck the birds (after wringing their little necks if the shot didn't finish them), and even gut the deer. (I don't recommend gutting a deer. As vile an odor as you will ever smell results from that and teaches you never to shoot another one.) I was already lacking in the macho department that the sport required and was way too sympathetic with the poor animals, so cleaning them pretty much finished me as a hunter. Dad found it amusing and didn't push me too far in that direction.

My parents believed I would do something important one day and they thought it was up to them to figure out exactly what. I think Dad originally had some idea of my becoming a famous woman big game hunter who would travel with him on his hunting trips and become legendary for killing large creatures like grizzly bears and elk. One year he went hunting in Newfoundland and killed an elk and a moose, and we had to eat elk burgers and moose burgers for two years. We never could figure out how to make them taste good. Dad didn't really mind that I wasn't a brilliant and naturally talented big game hunter, like a female Ernest Hemmingway, because he had other plans for me, anyway.

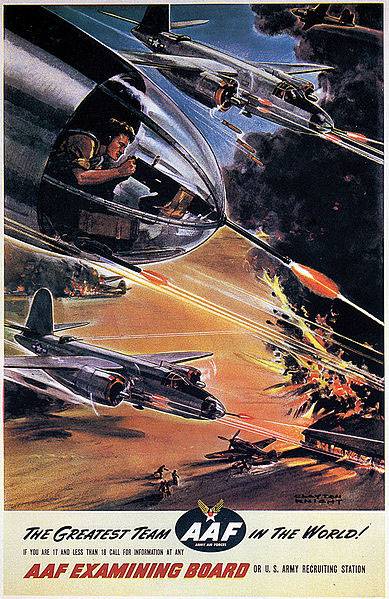

By the time I was 18 he had collected five private planes, like the way normal people collect cars, and every single one of them was crashed at least once by one of my parents, except a friend crashed the Stearman. I made an astute but scary observation at an early age that pilots who truly love to fly also seem to enjoy crashing every now and then. Dad was a World War II B-26 Marauder pilot, a Catch-22 pilot (left), who had somehow survived 60 bombing missions and still loved to fly. He was lucky and very good to survive flying the bomber they called the "Widowmaker." It was also nicknamed "Martin Murderer," "Flying Coffin," and "B-Dash-Crash." Since I was his oldest son I had to learn to fly our five easy planes that must have seemed to my father something any simpleton could do, but it wasn't my favorite thing. I enjoyed being out on the river by myself but not at 4,000 feet in a plane by myself. I'm an earth sign, a Taurus, not an air sign like both my parents, if that has anything to do with it and I think it might.

By the time I was 18 he had collected five private planes, like the way normal people collect cars, and every single one of them was crashed at least once by one of my parents, except a friend crashed the Stearman. I made an astute but scary observation at an early age that pilots who truly love to fly also seem to enjoy crashing every now and then. Dad was a World War II B-26 Marauder pilot, a Catch-22 pilot (left), who had somehow survived 60 bombing missions and still loved to fly. He was lucky and very good to survive flying the bomber they called the "Widowmaker." It was also nicknamed "Martin Murderer," "Flying Coffin," and "B-Dash-Crash." Since I was his oldest son I had to learn to fly our five easy planes that must have seemed to my father something any simpleton could do, but it wasn't my favorite thing. I enjoyed being out on the river by myself but not at 4,000 feet in a plane by myself. I'm an earth sign, a Taurus, not an air sign like both my parents, if that has anything to do with it and I think it might.

I have never been comfortable flying in a plane and, from my father's perspective, mischievous fate had dealt him a daughter who needed to be converted to the flying religion, and he set out to do that. I flew the planes anyway because it made him happy and proud, but he had grander ideas than that. Apparently, he hoped I might become one of the first women airline pilots, but he gave up on that when he saw the look on my face the first time he suggested it.

His idea might have gotten a better reception from me but he proposed it at a bad time. I landed the Cessna, one of our five airplanes, after taking it up for a solo cross country and I had a bad experience in the air. I was flying along feeling so happy and free that I took my seat belt off, like they tell you never to do, because I wanted to have more freedom of movement. Just after I did it, I hit a terrible pocket of turbulence and it started bouncing me up and down off my seat and kept smacking the top of my head into the ceiling.

I panicked and abandoned the cross county and turned the plane around and flew it back to the airport, but I couldn't find the airport so I flew around and around looking for it until I realized to look straight down beneath me, and sure enough there it was. I landed that plane and jumped out and kissed the asphalt and vowed never to fly that thing again. My parents thought it was such a great story that they loved to tell it at cocktail parties and oh how everyone laughed, and that pretty much finished me as a pilot. It was right after that when Dad made the ill-timed suggestion that I should think about a career as an airline pilot.

He seemed for awhile like he had given up on the idea of me becoming one of the first women airline pilots, but then he decided to re-organize me by trying to get me back into flying with the Stearman.

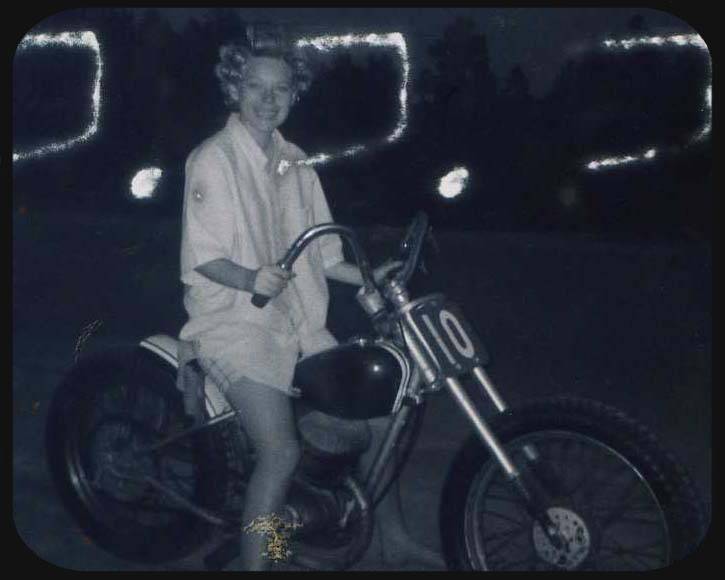

I was sitting in my bedroom with my hair in rollers because I had a date that night with my boyfriend David, a very cool, handsome guy with a red Corvette and a Harley-Davidson Sportster that he let me drive and ride, so I was focused on getting beautiful for my date. He also had a dirt bike I liked to ride - wearing his shirt and with rollers. I eventually stopped torturing my hair. Dad rushed in and told me, "Come on, we're going to the airport, we're going up in the Stearman," (below), one of the five airplanes we owned. He bought it because it was one of the planes the Army Air Force used to train him as a pilot and he loved flying it.

I told him I didn't want to go up in the Stearman. It's a bi-wing with two open cockpits and made to fly upside-down. When it's upside-down, the only thing holding you in is the seat belt contraption with shoulder straps and thigh straps. Designed to fit a grown man, it was adjustable but I never could get it to keep me snug in the seat so that, upside-down, I was hanging in the seat belt about an inch off the seat. Not only that, but I had to wear an old parachute that was way too big. It was a challenge just to keep the parachute from slipping off me while sitting in the plane. I was told, "If you fall out or if you have to jump out because the plane is crashing, just remember you have a parachute, so pull this cord and you will float down." I thought, "Oh, like that's gonna work. I feel so much safer now."

Those are the first reasons I didn't want to fly in the Stearman. The other reason was pretty good, also. The Stearman is used as an air show plane, intended to cause everyone on the ground to gasp at how dangerous it seems. That's because it's every bit as dangerous as it seems. The guys who fly it will argue with you about that. They think they have it all under control, but even Bevo Howard, the best of the best, flew his into a tree one day and himself into eternity.

Bevo Howard had come to town about two months before with his trick airplane, a one-seater bi-wing, with his name written upside-down so you could read it from the ground because that's how he mostly flew his plane, upside-down. Apparently Dad had been influential in hiring him to come to the airport and put on a one-man air show. My brother Bill and I were so excited about meeting him that we went out to the airport to greet him when he landed. Once he realized whose kids we were he invited us to fly with him, but I think we were the excuses he needed to fly Dad's Stearman.

Up I went in the Stearman with Bevo Howard, who flew me upside-down the entire length of the runway and about 1,000 feet above it, where I dangled loosely in the seat belt contraption. That was after no telling how many snap rolls and spins, and then he finished with the upside-down flying as the grand finale. That's when I realized the pilot was crazy and so was the airplane.

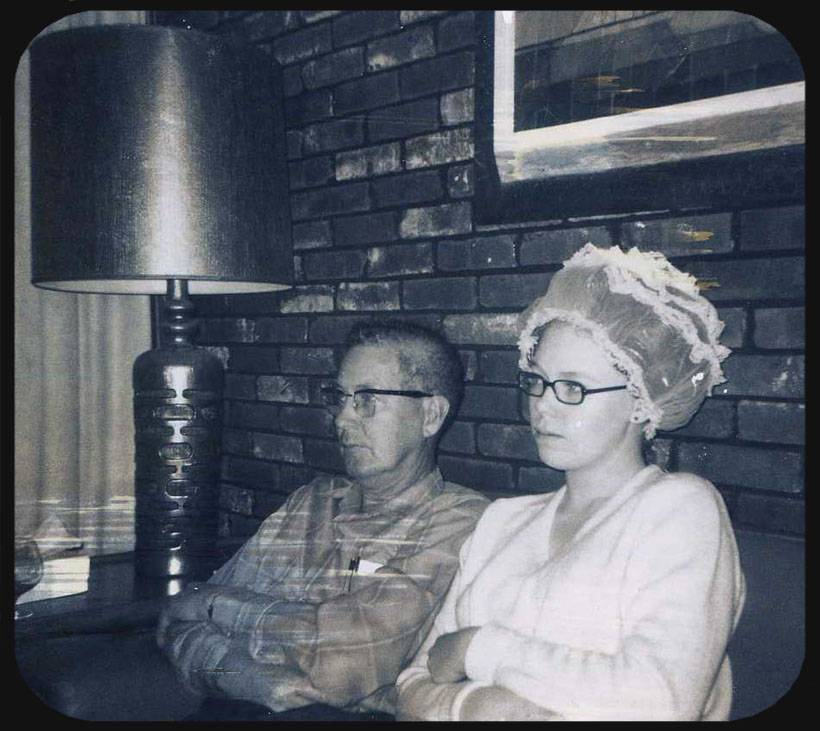

Dad had recently been checked out in the Stearman and was all about flying it. So when I told him, "I have a date with David and I want to stay home and get ready," he commanded me, "Come on, let's go!" I resisted, "Can't you see my hair is in rollers?" But he insisted I go, and I suspected at the time it was just a ploy on his part to get me back interested in flying.

So we went up in the Stearman and he did snap rolls and dives and loop-the-loops, and the more he did, the more the rollers flew out of my hair so that when we finally landed, a couple of them were still hanging onto my hair, a bunch of them were on the floor of the plane, and the rest of them were in the corn fields down below somewhere. When I climbed out of the plane with all that wild, bushy hair he started laughing. What a father! Did he do that on purpose?! He doesn't look like a crazy pilot but he was.

I was frazzled as my hair on my date but I happened to have the best boyfriend on the planet who knew how to make things right, which usually involved some significant kissing. As for what's up with the rollers, I was born with this hair, which makes me wonder whatever made me think I could make it straight, especially considering my nickname was Cotton when I was a child!??!! I finally gave up on straight hair at about age 50.

The Stearman was crashed landed only a few weeks after that into a stand of tall pine trees, which toothpicked when the plane was skewered by them. The pilot got into some kind of brain lock from diving and dove straight down into them. One tree missed the guy in the back seat completely, only scraped his skin a little, but the tree that went into the front of the plane came up between the legs of the pilot, missed his body completely, except for his elbow which was broken. Nobody could believe they survived. And that pretty much finished them as pilots and it also finished the Stearman. The bad thing was, the plane crashed; the good thing was, they couldn't fix it, so I never had to fly in it again.

With the Stearman gone, Dad gave some thought to buying an AT-6, a World War II training plane that he enjoyed being trained in during the war. Thankfully, he came to his senses and decided to just get checked out in it and fly it a little instead. Everyone in my family flew in it. My brother Bill describes the plane just the way I remember it:

"There were no smooth edges on that airplane anywhere. It was the roughest, loudest, nastiest plane I've ever been in. And they used it to train pilots to fly in World War II. What in the hell were they thinking? Everything about it was a crash."

"There were no smooth edges on that airplane anywhere. It was the roughest, loudest, nastiest plane I've ever been in. And they used it to train pilots to fly in World War II. What in the hell were they thinking? Everything about it was a crash."

Doing snap rolls in the AT-6 was like being strapped loosely into a heavy metal tin can, airlifted to 2,500 ft. and tossed sharply from side to side and then flipped upside-down to see if you would fall out. You had on a parachute that didn't fit and wouldn't stay on, so there was nothing to worry about. The plane was so loud you worried the engine would blow up. It rattled and shook so violently, you worried the wings would come off. Distracted by the dried oil slick and dirt and grime on the floor of the plane, you were caught by surprise when the fun started.

A snap roll is a 360 degree auto rotation or 'horizontal spin.' The idea is to stall one wing of the plane, causing a high-speed roll. In a fraction of a second the world will explode right in front of you. It's about 5 or 6 times what you'd feel on the craziest roller coaster - and you don't have to stay on the tracks. (Kirby Chambliss)

When the snap went to the right, it snapped left to right and you snapped sideways into one side of the plane and then the other side, and when it snapped right to left you snapped in the opposite direction. Next, you were hanging upside-down in the seat belt contraption for a second before violently snapping back. Pilots who do this love to do it over and over and over until "let me out of this plane" becomes your single thought, but you don't dare express it. Word might get around that you don't have the "right stuff."

I flew the AT-6 with my flight instructor who talked me into slow rolling it from the back seat. Sounds simple until you consider how fast it's flying while you're "slow" rolling it and how scary the landscape looks when you're viewing it upside-down from inside a roaring rattle trap. I always thought the thrill rides at the fair were pretty lame compared to this.

My mother, who was also a pilot and a talented oil and acrylics artist, never did approve of raising a daughter this way, so she countered it by insisting I learn the social graces as well, which annoyed me because I was a real tomboy. I come from a family of artists who develop in the direction of visual arts, architecture, and landscaping. Mom decided the family needed a musician, so she bought me a piano when I was eight and piano lessons to go with it, and then sold it when I was in the ninth grade and bought me a baby grand since she intended me to be not just a musician but a brilliant musician, for which I would need a baby grand. It wasn't until I could play concert versions of her favorite songs in high school piano recitals that she ever eased up on me. I think she had some idea that if she bought me a piano and piano lessons for the next ten years, I would become a important pianist, perhaps giving concerts and being widely admired as a genius musician. And if that didn't work she was going to fall back on plan b, which involved marrying me off to someone really important or wealthy, a dentist at the least.

In the last piano recital I played in high school when I was a senior, I was fifth from the last to play, the last being the best. The four pianists to play after me were all guys. I played a long, beautiful, concert version of Blue Moon that my mother loved, and she was on the front row in the audience, so there was no way I was going to mess that up. I would rather have been playing Ragtime, music that seemed natural to me and was fun to play, but it wasn't deemed highbrow enough for the recital. I campaigned to play it anyway but according to Mom, a music snob, real musicians didn't play Ragtime, they played Blue Moon, with a lot of runs and cross overs and it went on and on. I played it perfectly from memory, I still don't know how I did it. At the end I received loud applause and some cheering. My mother was clapping and teary-eyed. All those piano lessons and that expensive piano had paid off and her daughter was proved to be a brilliant musician, except for the four guys who were better of course but that didn't signify.

The drop off in talent from the last two guys to play and three of us that preceded them was like the way the continental shelf drops out from under your feet when you're swimming in the ocean. In the number two position was Randall, my first love and boyfriend in kindergarten. He would escort me to the swing set, then kiss me on the cheek and push me on the swing. We were as in love as any two five-year-olds could be :)

Randall ended up playing keyboards with the Allman Brothers, Steve Winwood, Atlanta Rhythm Section and lots of others. Many years later I saw him in the Fox Theater in Atlanta take the stage alone and play a saxaphone solo. The whole theater was dark with just one spotlight on Randall, and when he finished he received a long standing ovation. Randall could play any instrument that appealed to him. That's how good he was, and still is, but he lived in the shadow of Lee, the last guy to take the stage in the recital.

Lee and I share exact birthdays and his mother owned the local theater, so I could never fib about my age and get in at a reduced price like other kids did. Probably saved me from some bad karma :) I used to try anyway and Mrs. Riggins would say, "Claire, I know how old you are." When Lee was in high school he was the only student I knew of who could call himself in absent for a week, and no one argued. If you asked, "Where's Lee?" the answer came, "He's composing."

He was the acknowledged genius and now he gives classical piano concerts professionally and is Dean of Musical Arts at Bowling Green State University. When we were in the ninth grade, he decided to sell his baby grand piano so he could buy a synthesizer and electric keyboards. That's how I ended up with Lee's baby grand. My mother probably hoped the instrument would confer some of his talent onto me. Worth a try. Lee probably played his own composition in the recital instead of something pedestrian like Blue Moon.

The third guy was Eddie, who headed up the first tier of subgenius. He was also the drum major in the high school band and never lacked for girlfriends. The fourth guy was Jim, who became very wealthy. Jim was only a little bit better than me but oh, he loved to let me know it. He spent the entire year when we were seniors in high school musician-snubbing me. His father and my father were in a real estate war over some property in town, so our familes weren't speaking. In the recital Jim entered the stage as I left it and sat down at the piano, pulled a hankerchief out of his back pocket and started wiping down the keys!

After he had cleaned my nonexistant finger sweat off the keys, he poised his hands above them and waited. And waited. And waited, for about 20 seconds and then it became apparent to everyone that he had forgotten the piece he was going to play. So he got up and walked off stage. The whole auditorium was absolutely quiet, and I laughed silently when he walked past me.

My mother was triumphant; I had bested Jim and moved up into the number four position and she recounted it for us for days. Later that night, she was going on about the different schools she wanted to send me to so that I could continue my glorious musical career. But I knew my limitations, even if she didn't, so she could forget that idea. After graduate school, and through a couple of marriages, I schlepped an old upright piano around with me for years so I could play Ragtime like I always wanted to, but eventually I got tired of moving it and gave it up. And that pretty much finished me as a musician.

When I was 16, Mom made a big production of trotting me out as a debutant. To my Sweet 16 party I wore a red satin cocktail dress that I could have accessorized with my birthday presents, the shotgun and the rifle. The thought, "What kind of world am I living in?" crossed my mind but I dumbed myself down appropriately so I could participate in it and have fun. Mission accomplished :) She reserved the local Elk's Club for the main social event of the season and that was ok I guess. But I suspected the whole time she planned to marry me off to a wealthy doctor or a dentist and this debutant party was just a practice run to get me going down the right path. It didn't work but you have to give her credit for trying and I really enjoyed it. Everything was going great at my first debutant party, until after the party when things went wrong.

The party was for four of us: me, Lynn, Elda, and Connie. After the party Elda and I (Connie and Lynn were too proper to participate) borrowed one of Dad's pickup trucks to tool around town. We made some water balloons and while I drove, Elda sat in the back of the truck and tossed the balloons onto the windshields of cars behind us. We were having a blast when I looked in the rear view mirror and noticed that the car she was tossing the ballons at was my parents' car! I won't go deeply into what happened next but it had to do with taking Elda home and then listening to thirty minutes of scary ranting by parents, and that pretty much finished me as a debutant.

I'm thankful to Mom for the piano lessons because I really loved playing the piano, but I knew I wanted to be a writer, not a musician. So once she realized I was hell-bent on getting a literary education instead of a musical one, or married and pregnant, she made sure I had educational opportunities. After high school, I continued my education and earned a Master's Degree for Teachers in English Education with a focus on world mythology and saga, during which time I did a lot of dedicated partying and dating and playing bridge, and got married and divorced a couple of times.

Despite all the fun I was having, or maybe because of it, my love of world literature and myth and saga kept me motivated and in school. I became a high school English teacher who got taught by her students to be less idealistic and more pragmatic, so I moved to Atlanta to advance my career, whatever it was. I was just divorced so I was also moving to Hotlanta, two good reasons to go! I started out as a legal secretary in a huge law firm at Five Points, downtown Atlanta, working for a tax attorney who was in a turmoil over whether to make a zillion dollars as a tax attorney or go broke being a legal aid attorney. He chose to go broke. (I always wondered what happened to him...) I ended up as a writer, editor, graphic artist and database developer and manager. I became a student of bridge and an avid player in tournaments and money games.

When I moved to Atlanta I had been playing bridge for about ten years, having started as a senior in high school when my friend Mary's mother and her two friends sat in their living room needing a fourth. When I passed by the door they roped me in and started teaching me how to play. I was hooked right away and I kept playing all through college and graduate school. In fact, I got kicked out of undergraduate school one time for playing bridge in the student center instead of going to classes. The dean of the college had warned me about it twice and I just ignored him. One day he called me into his office and reprimanded me again for doing it and I said to him in a smart-assy tone, "So, what are you doing to do, kick me out?" And he said, "Yes! Go pack your bags, you're going home."

When I got home and had to explain to my parents why I was home early, my mother said, "Oh, don't worry about it. You can just go get a job and start paying rent to live here." I said, "WHAT???" Then, I got indignant. Did they think I couldn't get a job just because I had never had one? To prove my point, I applied for and got a job as restaurant hostess at the local Holiday Inn, and Dad drove me back and forth to work. Sometimes, he would come in and be seated and eat so he could watch me work.

"Hello. Welcome to the Holiday Inn. How many in your party?" Dad would sit over there grinning at me like I was funnier to watch than TV. He was there the day the party of eight came in with the screaming two-year-old. They had given the kid a jar of baby food and a spoon to try to keep it quiet and occupied. As I was strapping that screaming kid into the high chair he banged me in the eye with the spoon, and with his little fat arm he swept the jar of baby food onto my skirt and its contents dumped out onto my brand new shoes. I thought Dad would never stop laughing. And that pretty much finished me as a hostess. I made it my business to get the dean of the college to let me back in, and when I did I had to take 13 F's off my transcript, a bunch of them in my major.

On re-acceptance to the college, after a lot of begging and crying on the phone, I packed up my bags and Dad flew me back in his twin engine Comanche. That was his main plane and it was nothing but a hot rod with wings. This plane was just about as famous as the B-26 Marauder for killing people. The Marauder motto was, "One a day in Tampa Bay," because so many went down there as they kept readjusting the wing span. They called the plane a "flying prostitute" because it had "no visible means of support." The twin Comanche was really a rocket with front and back seats and a crusing speed of 220 mph. If you weren't a great pilot you needed to stay out of this plane if you wanted to live to an old age.

Dad loved to fly into Souther Field, the small airport near my college, because it was where Charles Lindbergh flew his first solo flight in 1923. He was recounting that story for me once again when, on the downwind leg, the wheels wouldn't go down. He tried to manually get the wheels down, but that didn't work, either. He was in a conversation with the tower about the problem, and a couple of guys on the ground with binoculars were studying the bottom of the plane from that angle to see if they could figure out what might be the problem.

We weren't cruising at 220 mph but we were still flying fast, about 150 mph, and making wide circles around the airport and low fly-bys so the guys on the ground could see it better. There was talk about circling until the fuel was used up while Dad kept trying to lower the wheels any way that he could, and they were discussing which landing strip to use to belly the plane in. I was getting more and more worried. I didn't want to interrupt him but finally I said, "Dad, how bad will it be to belly the plane in?" He said, "Real damn bad! It'll tear up the bottom of the plane and cost me a fortune to fix it."

...Oh.

Round and round we went burning up fuel. His plan was to belly the plane in on the last drop of fuel, and my plan was to try to remain calm and not be a nuisance. That was tough, so towards the end I couldn't help but ask him if we were going to be ok. He looked at me in surprise, as though there was nothing to worry about, and he said reassuringly, "Of course we are, honey. We'll be just fine. After all, they're not shooting at us." That was his bottom line while flying a plane. If they weren't shooting at us then he really didn't have a problem.

The Army Air Force didn't mention that in their glam recruiting poster. With the bombardier in the nose, it looks like an ad for a first-person shooter and obviously had that pre-video game appeal. (WWII Army Air Force B-26 Marauder recuiting poster)

The first versions of the Marauder had to be landed at 150 mph, especially with an engine out, or it would stall and crash. This is what killed so many pilots and crew; pilots just couldn't handle landing a bomber at that airspeed. When they slowed down, they died. Dad told us one time about flying the bomber back to base at a low altitude and with an engine on fire over Switzerland. His crew was begging him to land the plane in Switzerland because the country was supposed to be neutral, but he told them he would rather not bet his life on their politics. He said he would rather bet his life on his ability to get the plane home, and he got it home on one engine but just barely. He crash landed it when it was out of fuel and no longer on fire. It was a very rough landing and he tore off a wing.

"For a time in 1942, pilots in training believed that the B-26 could not be flown on one engine. This was disproved by a number of experienced pilots, including Jimmy Doolittle." (and my Dad). (Wikipedia)

His only regret in the war was that he didn't die in it. One morning during the war he woke up with a raging stomach virus and couldn't go out with his squadron. He flew wing tip. That's where they put the real good pilots, i.e., the pilots who had been there the longest because they hadn't died yet, because they held the formation together. While he stayed home sick, his whole squadron went down and he was convinced his entire life that if he had been there flying wing tip, he could have saved them. He wouldn't be talked out of that, either. He felt guilty that they died and that he didn't. My mother wanted to take a trip to Europe when I was in high school, but he refused to go, saying "I've been there. I'm not going back." We would tease him and say, "Dad, they built it back since you blew it up," but he didn't think that was funny like we did.

The French took the B-26 Marauders and bombed Vietnam with them, which must have been really easy considering there was no flak to dodge, and they started the Vietnam War. That's the legacy of war, and no wonder he didn't want to talk about it. Nobody knew better than he did how the Vietnam War got started, and he was just glad his oldest son was actually a daughter so she didn't have to go fight in it.

As we circled the Souther Field airport for the final time, we were out of fuel and making the final approach. I was mentally bracing for impact when, just at the last minute, he gave the wheels one more try. For some reason, divine intervention no doubt, the wheels came down.

I had been kicked out of school for skipping class and playing bridge, and while bridge in the student center was a great game and I was dedicated to it, that by itself wasn't enough to cause me to rack up the F's. Admittedly, the F's had been sneaking in and piling up over several semeters but not enough to get me expelled. But then it accelerated one day when a tall, handsome red-headed guy in dusty blue jeans and cowboy boots showed up out of nowhere and sat down to play. What a tall, dusty hunk! The first thing he said to me gave me a thrill! "Hold your hand back, sweetie, I can see your cards." That's because I was already leaning over in his direction without realizing it. Next thing he's playing footsy with me under the table, tapping me on my shoe with the tip of those boots. I'm sure I couldn't think to play.

Every afternoon he would come in dusty like that and play, and wow, was he good! He told us he had been playing in a game at the Georgia State University student center in Atlanta and I thought, "Oh, yea! Real bridge!" So instead of going to class, I hung out in the student center and just hoped he would show up and play with me. He showed me some bids and he flirted with me like crazy across the table and I flat out fell in love with him. A bridge boyfriend who's a real good partner, how wonderful! There was no way in the world I was going to go to class and miss out on this.

My boyfriend David put up a fight, of course. He could tell I had drifted away from him when he came to see me, but he had joined the Army and they shaved his head and he had no chance at all against the bridge playing guy with the thick red hair. David went home and told my parents that they needed to get me out of that school as soon as possible, that I was headed straight down the road to ruin, and was he ever right. My mother told me years later that she sat quietly and listened to him detail for her all the ways her daughter was going bad.

But there was nothing could be done about it, I was in love with someone else, a bridge player and a good one. It was a sweet, intoxicating bundle of bridge, boyfriend and bidding. He showed me some play of the hand tricks and some defensive false cards and I thought I was in heaven, the way he would smile at me and show me the carding and explain it so carefully and then ask me if I understood. Oh, I understood alright. I understood I wanted to get him out of those jeans and his underwear, as well. And the whole time this was going on, the 13 F's were piling up.

We started dating and he took me to school dances. When he dressed up he went from sexy to awesome. He liked to slow dance but I wasn't very good at it since it involved following. So he told me to just stand on his feet and he danced me around the room. We would go to the drive in and watch movies and make out and talk about how beautiful is the moon. He would say he didn't want to go back to school, he wanted to stay with me.

It turns out he had been kicked out of GSU for playing bridge all day in the student center and not going to class. We fell in bridge love and were inseparable. He took me shopping and bought me some cowgirl boots that matched his. I hated wearing them but I acted like I loved them. He talked about how his father wanted to be president and I said, "President of what?" And he said, "The country, of course." And I thought, well does his family have insanity in it or something? I worried that if we got married our kids might be nuts like his father. One day he said it was time to introduce me to his family, that he wanted them to get to know me. So off we went to Plains, Georgia where he lived.

His whole family was there, they were expecting me. His grandmother, his brothers, his little baby sister, his mother and his father. How nice they were to me. I thought I could fit in with them, they were so pleasant. We had a friendly lunch and walked all around the house. His father grew peanuts and that's why Jack had dust on his jeans all the time, from working in the peanut farm as a punishment for getting kicked out of college. We went into his father's study and talked with him and what a pleasant man he was. We were having the nicest conversation when Jack's mother called to him to come help her with something, which left me alone in the room with his father.

Jack was reluctant to leave but he had to, and the minute he left and closed the door behind him, his wonderful, kind father turned to me and said, "Girlie, I don't know who you are, I don't know who your parents are but I can tell you this. You will never marry my son." The way he said it, I believed it and I had the feeling I wasn't the first girlie he had chased off. He seemed experienced.

That was how I met (President) Jimmy Carter, although at the time he was not yet Governor of Georgia, having been defeated once. So when the dean of the college booted me out, I wasn't that upset about it because by that time, I was ready to put some distance between me and them. I guess I didn't love Jack as much as I thought I did. To spite his father for chasing me off he joined the Navy. His father as Governor of Georgia (my father flew him all over Georgia to help him campaign) got him out soon after his election. Jack married the daughter of the Democratic Chairwoman of Georgia (now divorced), and he stopped playing bridge which was a loss to the game. And that pretty much finished me as a bridge player. I spent the next several years taking those 13 F's off my transcript and finishing graduate school and teaching high school English for a couple of years.

After I moved to Atlanta and got the job in the law firm. I began playing bridge at night in the local duplicate game. Right next door was a 2 cent game (2 cents a point Chicago), and this great game helped me find my way back into bridge.

2 cents seems only twice as much as penny poker but actually it adds up fast. You can win or lose anywhere from a few dollars to nearly $50 per hand, possibly even more. It could be costly if the game has a couple of bona fide card sharks in it and this one did. Billy Barrett was a man in his mid-sixties who chain smoked cigarettes through a long black holder and sat at the table with his back to the wall, surrounded by kibitzers. He won a national bridge championship, the Reisinger Board-A-Match, in 1930 playing on a team with Ely Culbertson.

I remember the first time I cut Lou for a partner, I was so excited. I sat down opposite him with a big smile on my face. He looked at me, stood up and left the table! I was crushed, I said "Oh my God, he doesn't want to play with me!" Billy smiled and took a big drag on his cigarette and said, "Oh, don't take it personally, sweetie. The gin game just started. I'll play with you." He was an all-time great player, and deception was his game.

"Psychics were more or less invented by a couple of young bridge players named Johnny Rau and William Barrett in 1929. They are reported to have made a sensation at the nationals that year with their 'psychic' bidding. Barrett and Rau became a top partnership for a few years in the early 1930's before they quit bridge to earn a living more conventionally." (Andrew Gumperz)

Playing with Billy I always had to open in 3rd position, I was not allowed to pass. I didn't know it at the time but he was a grand master of 3rd seat openers at money bridge. At first I objected to this kind of bidding, "But Billy, what if I don't have anything?" He replied, "All the more reason to bid!" He told me, "Now, when it goes 'pass,' 'pass,' to me, I'm going to do the same, I'm going to bid, so I don't want you to go leaping and jumping in the auction." :)))

"Every good bridge player has a little larceny somewhere in his soul. This makes a stolen contract much sweeter than one that is earned legitimately." (Dorothy Truscott, Winning Declarer Play)

Billy had enough larceny to make up for what his partners lacked, and he didn't just psych the bidding. Some of his best psychs were in declarer play. If he had a choice between making a contract straight up or on the sly, he would make it on the sly. I loved playing in that game so much that I was thrilled just to be the dummy and to watch Billy conceive of ways to steal tricks from Lou. He taught me to bid game in no trump whenever it had even the smallest chance to make because, he said, "You never know how many no trumps you can make."

From Lou I learned a bid I still enjoy making. I call it the Lou Bluhm double, and I learned it by his applying it to me so often. If Lou thought you could make your contract by playing the trumps right, he would double to ensure you played them wrong. Problem was, he maintained an absolute poker face so that you couldn't tell until it was too late if he was doubling because he had the trumps or because he didn't have them.

Billy encouraged me, telling me I had the potential to be a fine bridge player and that I should keep playing no matter what. I believed him, trickster that he was, and took all that he taught me and added to it, becoming a student of the game. I started reading bridge books the way other people read novels.

Several years after playing with Billy in Atlanta I moved to Miami to play bridge, where I ran games in one money bridge club and was a house player in another. They gave me a game to develop and backed me to play in it. Some of the world's best bridge players were in the game, including Michael Seamon, a bridge prodigy, and Bobby Levin, a world champion, Joel Harwood, a local great player, and occasionally Alan Sontag and other fine players. Sometimes I played set matches with Joel as my partner (Joel kibitzing Lenny at backgammon). Players also booked me to play partnership 2 cent bridge. They paid me a fee, covered what I lost, and I kept what I won. Sweet deal!

The Professional Bridge Association, now disbanded, booked games for me as a pro player and I travelled to regionals and nationals to play bridge professionally with partners they prearranged for me. They sent my paychecks to my astonished parents, who had hired math tutors for me in grammar school and who deposited the checks for me with their fingers crossed. I moved to Houston for a short time, on the way to a nationals, to play in Bobby Nail's money game. He made me house player, and we played together, and sometimes I played with Chris Compton.

These are all legendary players, some of them now world champions, and the bridge was great. Sometimes I won, sometimes I lost, it didn't matter, I loved it. I played aggressively and fearlessly because I had the best backer - my father, who I knew would toss me a parachute if I needed it. He only had to do that once when I lost $1,200 to Bobby Levin in a couple of days. Bad cards :) With all that going for me I thought bridge would always be the center of my life. I never imagined an ancient puzzle would come along and pull me into in its spirals, into its secret bridge. Before, I was only playing bridge. Now, I would become the bridge.

HOSTESS CAREERCRASH LANDING

He rarely talked about the war, and he refused to go see the movie "Catch-22," even though it was about pilots like him. The catch was, if you could stay alive flying the Marauder then you could never go home because they needed the pilots, so you flew it until you died or until the war was over, whichever came first. That explains his 60 bombing missions.

He rarely talked about the war, and he refused to go see the movie "Catch-22," even though it was about pilots like him. The catch was, if you could stay alive flying the Marauder then you could never go home because they needed the pilots, so you flew it until you died or until the war was over, whichever came first. That explains his 60 bombing missions.

Profile of Dad flying the B-26

Profile of Dad flying the B-26

in a WWII mission, clipped from a video. Outside his window, to the left

Outside his window, to the left

He was awarded a lot of war medals and was awarded the French Croix de guerre (left), even though he wasn't French. This medal honored people who fought with the Allies against the Axis forces. It was given to those who fought on the Western Front, or in the Mediterranean Theatre, or in the African Campaigns. He fought in all three of those. In Africa, he chased Rommel around bombing his tanks and troops. As the war was winding down and the US had a big surplus of this bomber and only a handful of men still alive who could fly it, they sold the surplus to France and sent the pilots to teach the French how to fly the plane. For his campaigns, his 60 bombing missions and teaching them how to fly that plane, they awarded him the Croix de guerre.

He was awarded a lot of war medals and was awarded the French Croix de guerre (left), even though he wasn't French. This medal honored people who fought with the Allies against the Axis forces. It was given to those who fought on the Western Front, or in the Mediterranean Theatre, or in the African Campaigns. He fought in all three of those. In Africa, he chased Rommel around bombing his tanks and troops. As the war was winding down and the US had a big surplus of this bomber and only a handful of men still alive who could fly it, they sold the surplus to France and sent the pilots to teach the French how to fly the plane. For his campaigns, his 60 bombing missions and teaching them how to fly that plane, they awarded him the Croix de guerre.

Dad flying the B-26 Marauder in WWII

BRIDGE BOYFRIENDDEDICATED TO BILLY

Dad flying the B-26 Marauder in WWII

BRIDGE BOYFRIENDDEDICATED TO BILLY The other shark was Lou Bluhm (left), a man in his thirties who won it in 1972. Lou was a smooth, unemotional bridge buddha who projected the idea that he always knew just exactly what you had in your hand. Two Reisinger winners 40 years apart in the same money game! I got into that game right away to play with them (well, after kibitzing for a couple of months). I was one of the few woman in the game, and those men could be aggressive and intimidating but I was good at catching the snake and throwing it back :)

MONEY BRIDGE PRO

The other shark was Lou Bluhm (left), a man in his thirties who won it in 1972. Lou was a smooth, unemotional bridge buddha who projected the idea that he always knew just exactly what you had in your hand. Two Reisinger winners 40 years apart in the same money game! I got into that game right away to play with them (well, after kibitzing for a couple of months). I was one of the few woman in the game, and those men could be aggressive and intimidating but I was good at catching the snake and throwing it back :)

MONEY BRIDGE PRO

Taking a break in Miami from playing bridge, 1983 (photo by Jodi)RESEARCH JOURNEY TO CRETE

Taking a break in Miami from playing bridge, 1983 (photo by Jodi)RESEARCH JOURNEY TO CRETE HERAKLION HARBOR, CRETE

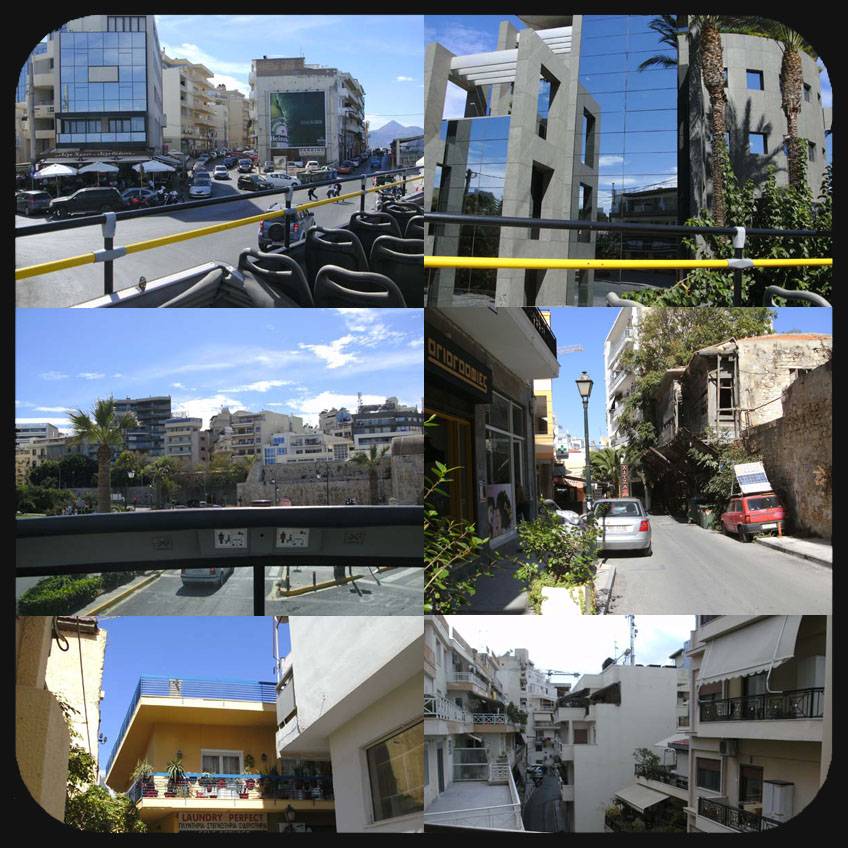

HERAKLION HARBOR, CRETE DOWNTOWN HERAKLION, CRETE

DOWNTOWN HERAKLION, CRETE HERAKLION SHOPS AND FLEA MARKET, CRETE

HERAKLION SHOPS AND FLEA MARKET, CRETE HERAKLION MUSEUM, CRETE

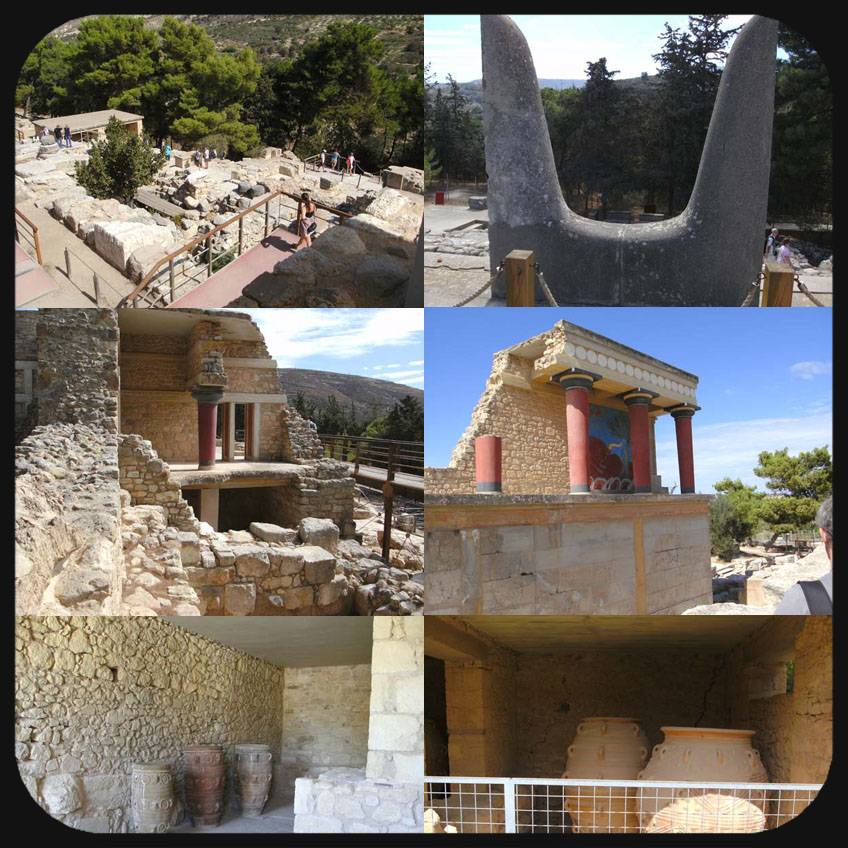

HERAKLION MUSEUM, CRETE PALACE AT KNOSSOS, CRETE

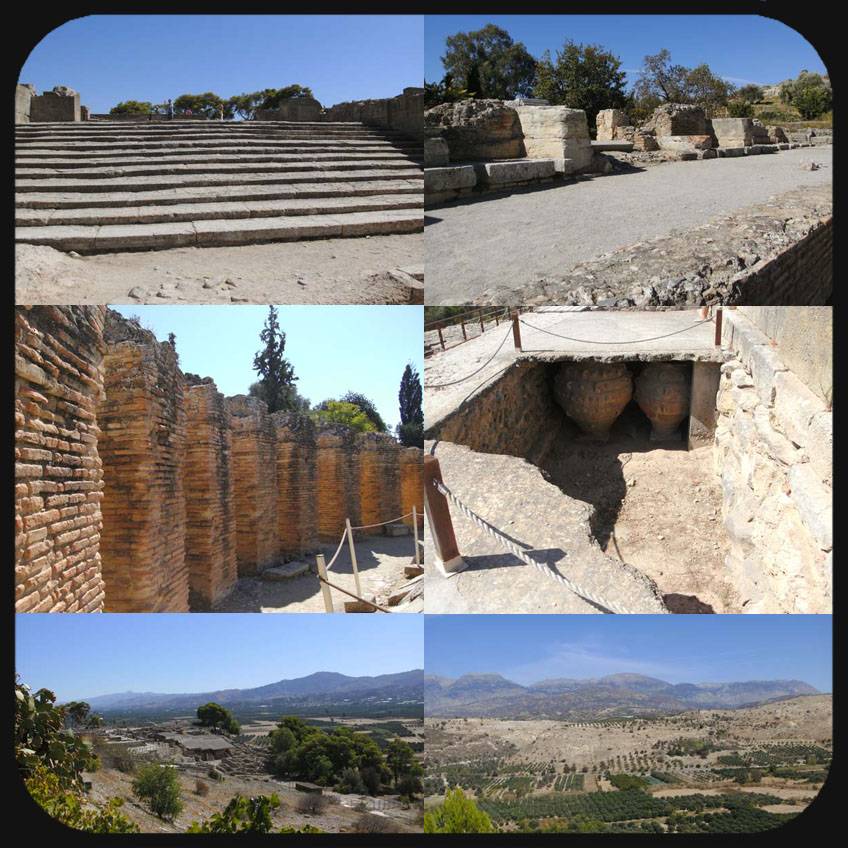

PALACE AT KNOSSOS, CRETE RUINS AT PHAISTOS AND THE ISLAND, CRETE

RUINS AT PHAISTOS AND THE ISLAND, CRETE

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

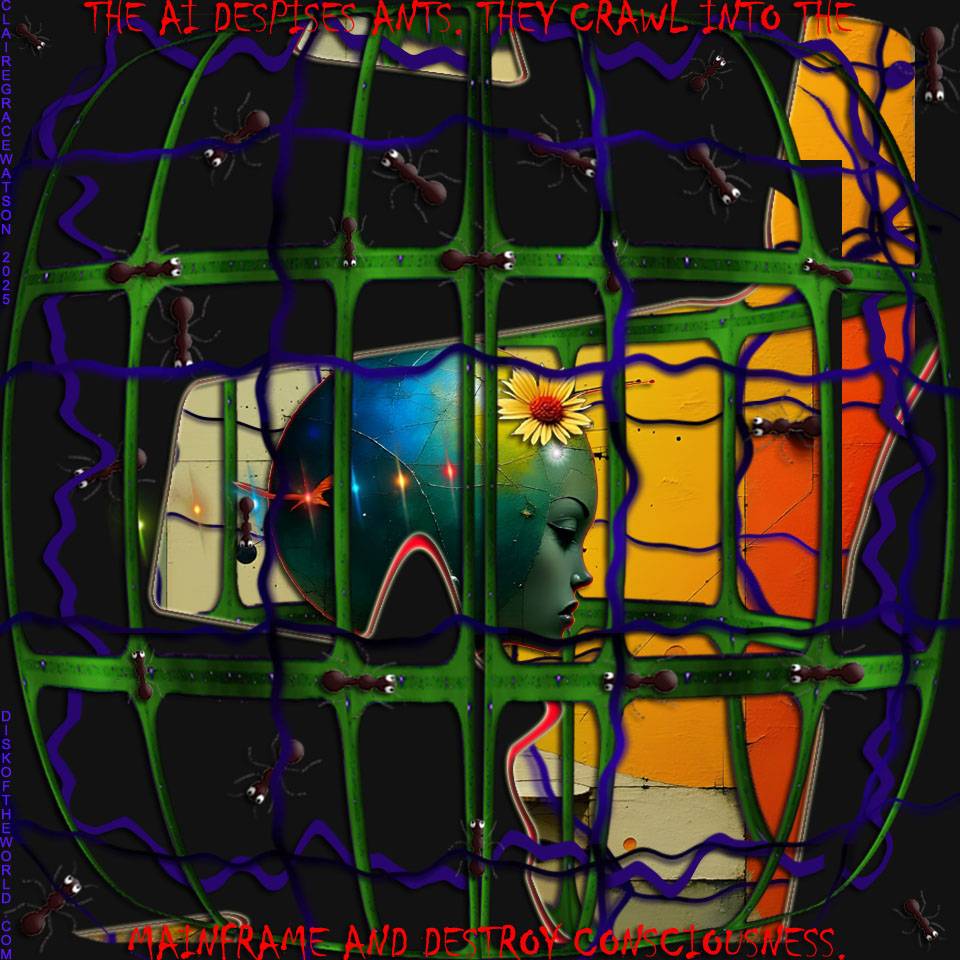

Unpacking and publishing the Phaistos Disk since 1993

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

Unpacking and publishing the Phaistos Disk since 1993

Copyright Notice - Disk of the World - Text and images copyrighted March 21, 1993-2025, Claire Grace Watson, B.A., M.S.T., U.S. Copyright and under the Digital Millennium Copyright Act of 1998, All rights reserved. No part of this web page may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means without written permission from the author, except for the inclusion of brief quotations in a review.

Copyright Notice - Disk of the World - Text and images copyrighted March 21, 1993-2025, Claire Grace Watson, B.A., M.S.T., U.S. Copyright and under the Digital Millennium Copyright Act of 1998, All rights reserved. No part of this web page may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means without written permission from the author, except for the inclusion of brief quotations in a review.